So… What does it all mean?

The implications of the above analysis for businesses, policy makers an investors are multifaceted and complex.

In a subsequent note, JMP Knowledge Lab will examine in more fulsome detail what it means for the economy and your investment strategies.

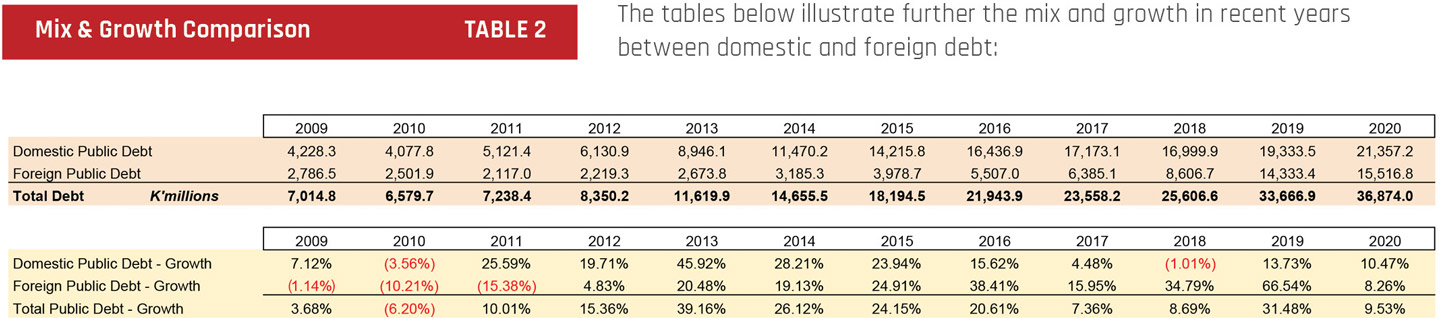

At this stage, suffice it to say that public borrowings can be a catalyst for positive developments.

It allows the State to smooth out volatile cash flows, provide economic stimulus at times when it is needed – such as during a global pandemic – and it plays an important role in delivering public investments which have the potential to drive welfare outcomes for our people as well as enhancing the productive capacity of the PNG economy.

The trick…..as they say…..is to make sure not to overdo it!

So far, there are probably no screaming alarm bells ringing, however finding that path back to a balanced budget is important in the medium term.

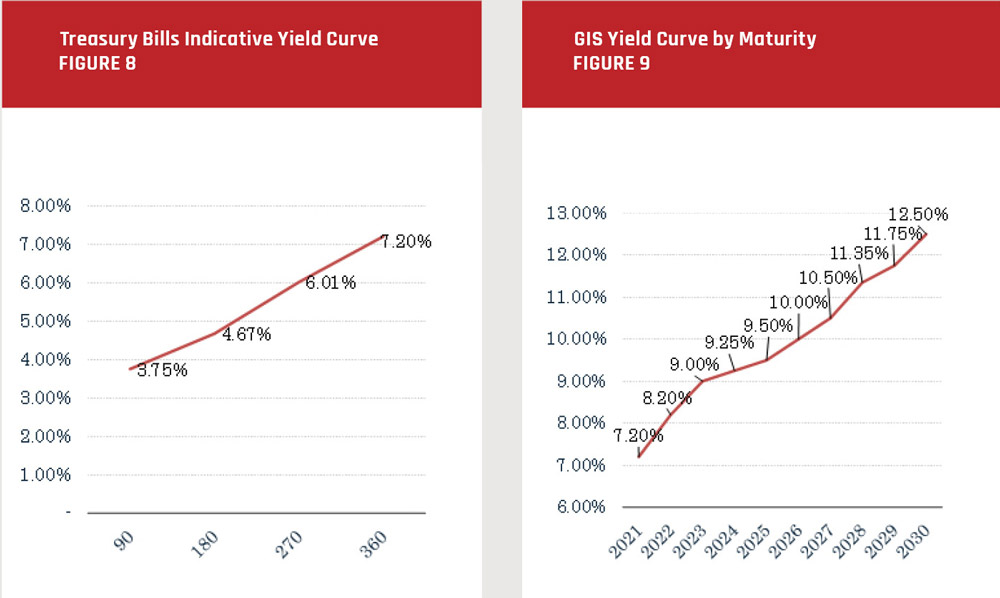

The global bond markets seem to agree with us, with yields on PNG’s inaugural sovereign bond which matures in 2028 not exhibiting signs of market disquiet at this stage.

But we do know that financial markets, global or local, can shift their sentiments quickly.

And the more drawn down we are, the less room there is for error or to move if circumstances were to change.

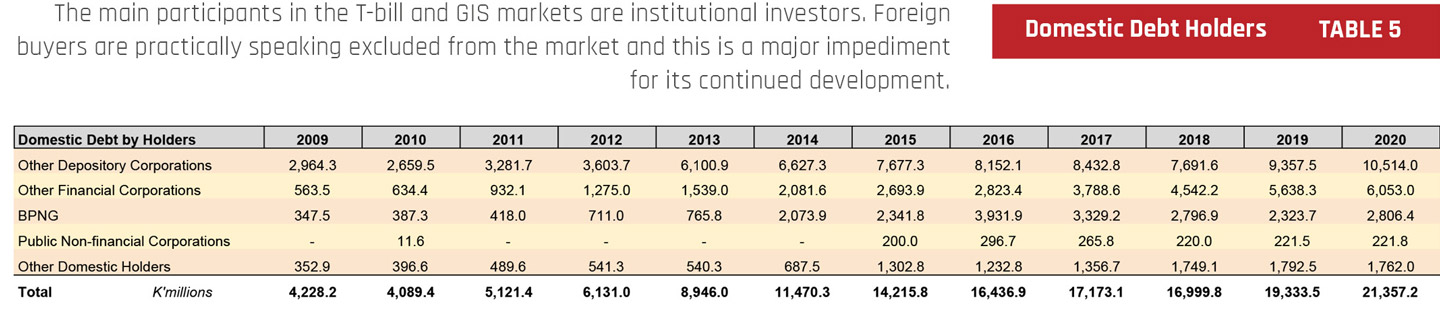

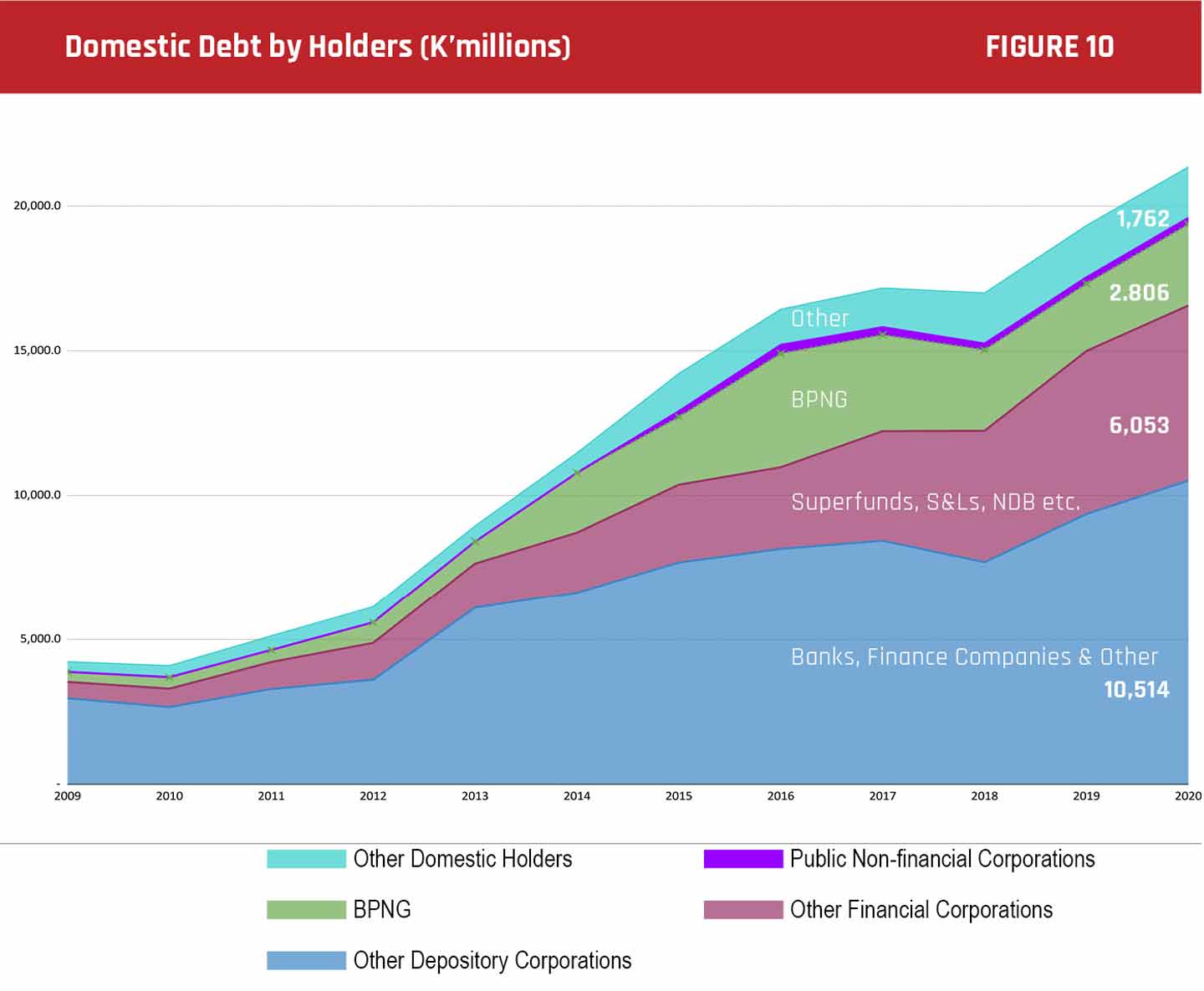

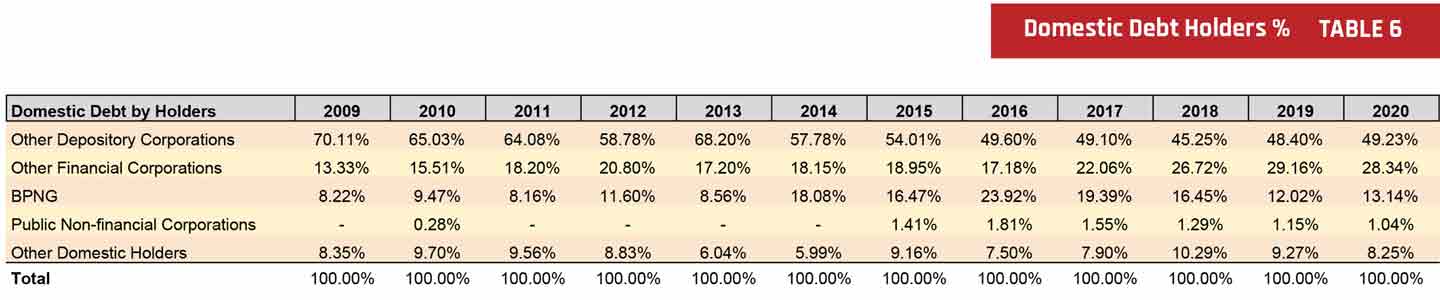

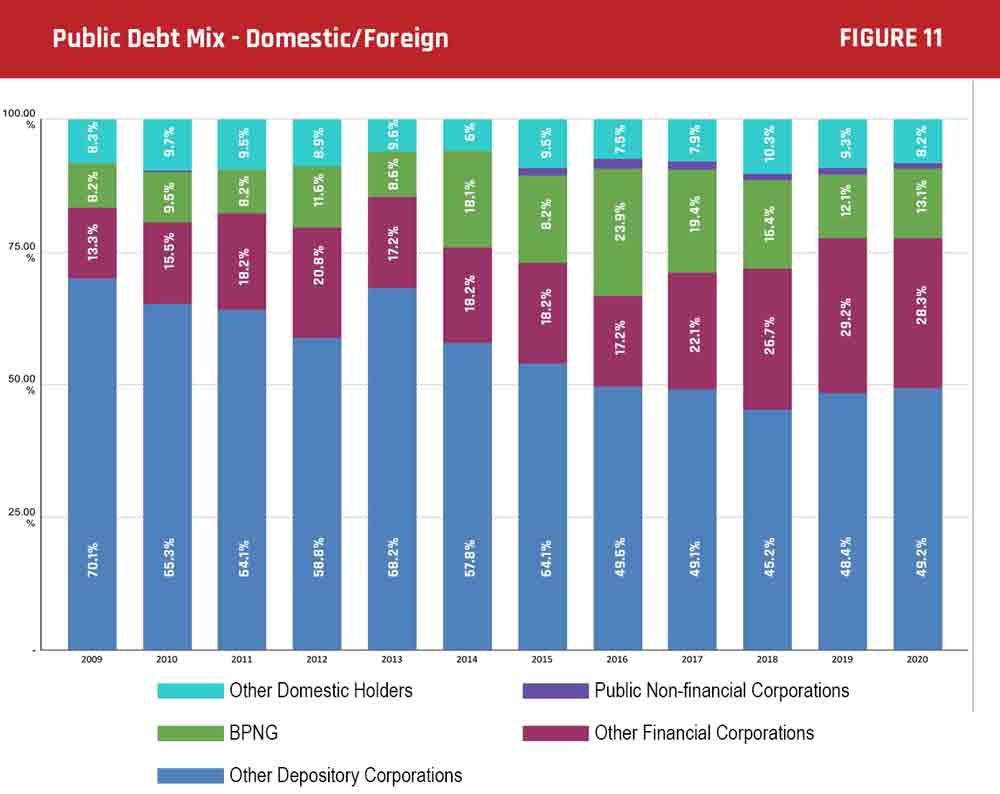

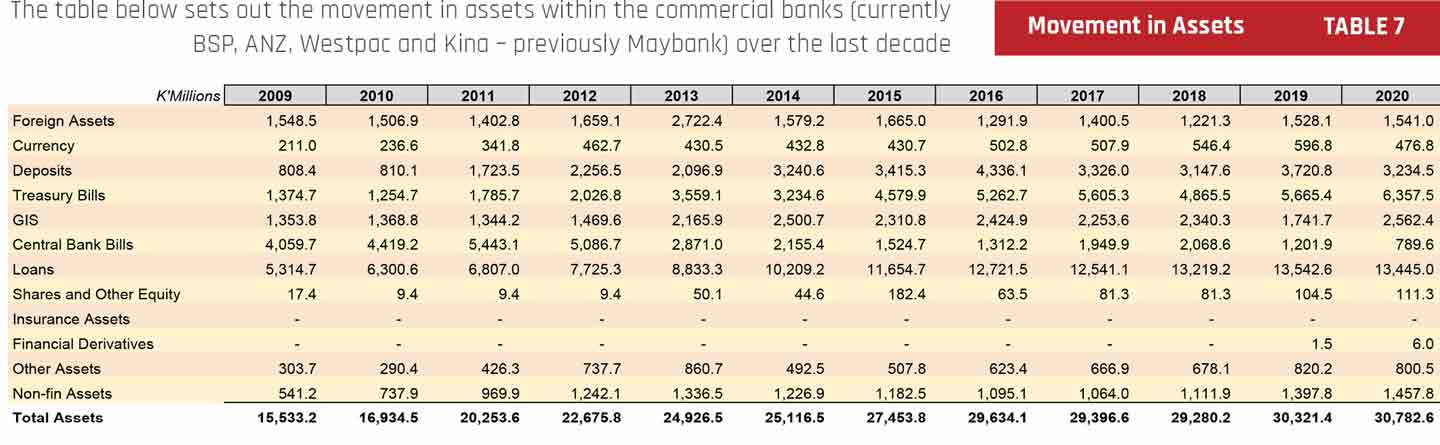

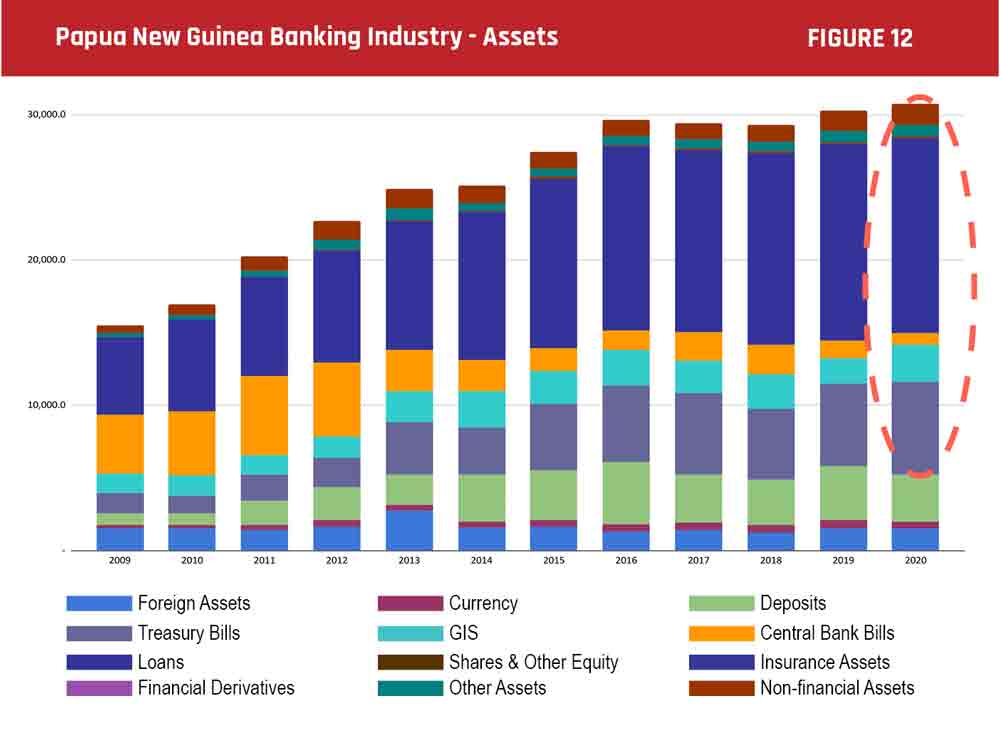

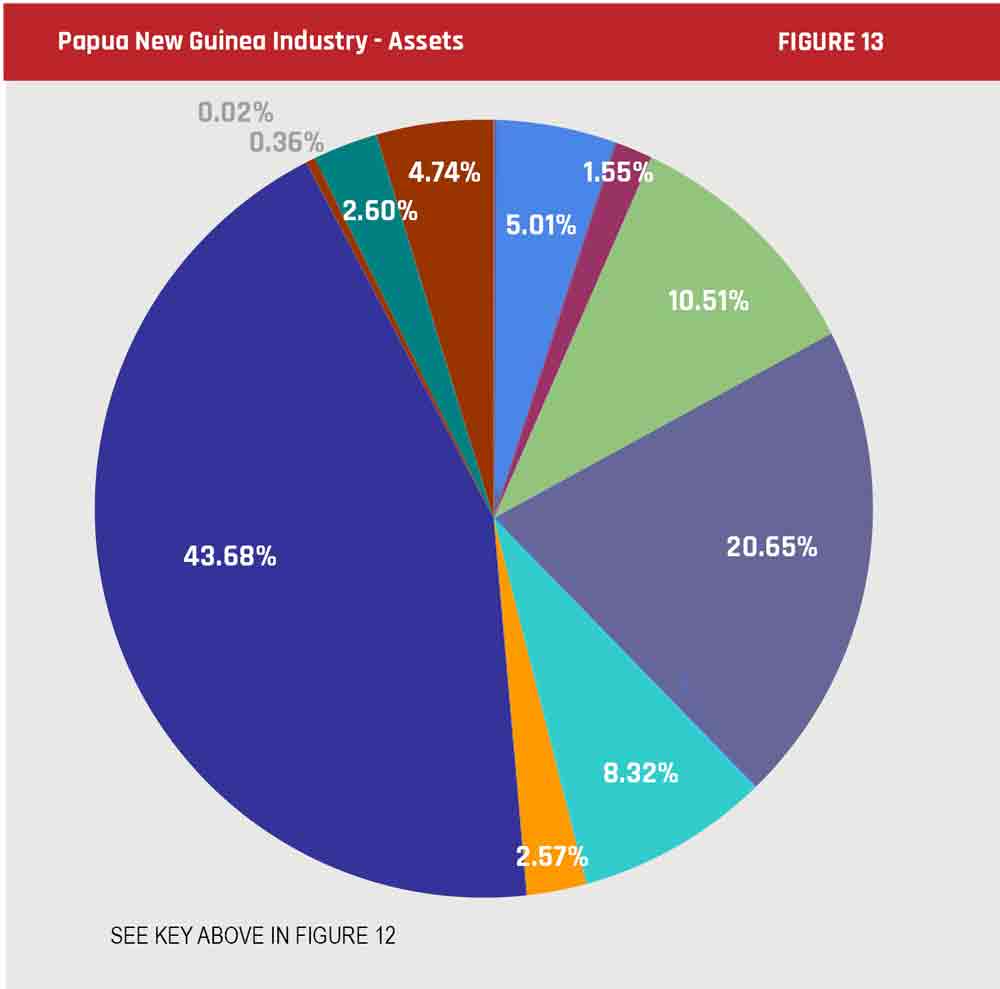

Even locally and in local currency, we must be mindful that the pool of capital available for us to draw from is limited.

To add to this, we must never forget that you can only borrow money for as long as someone is willing to lend to you.

In global markets, the pool of funds is practically limitless, but the segment that has appetite for our type of credit is much more limited.

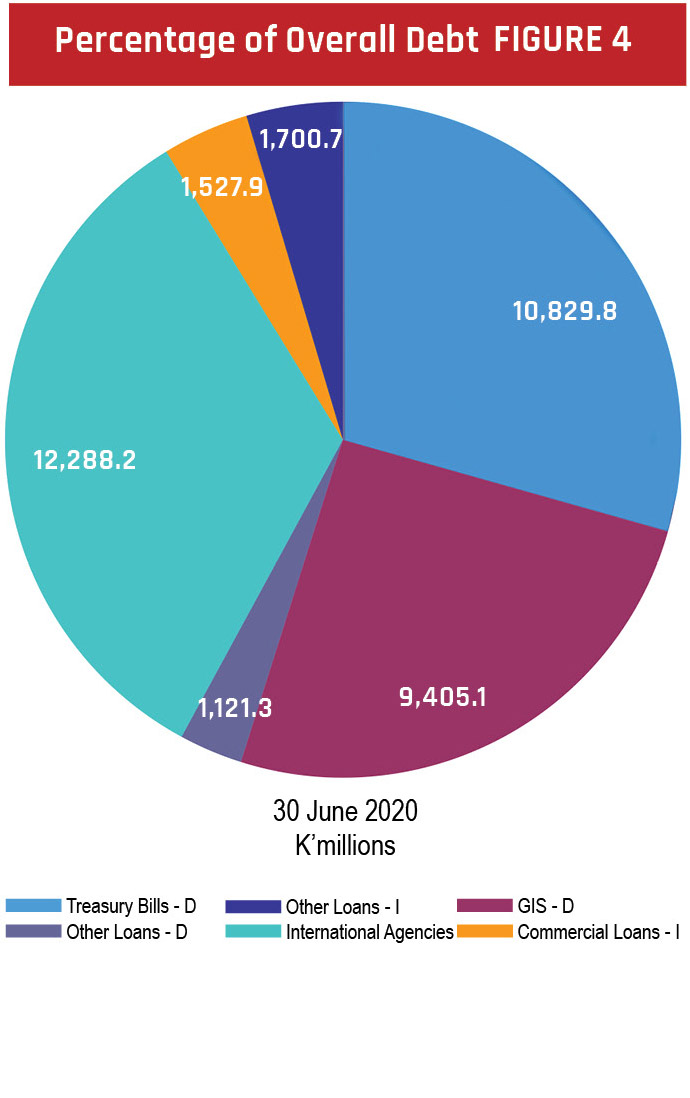

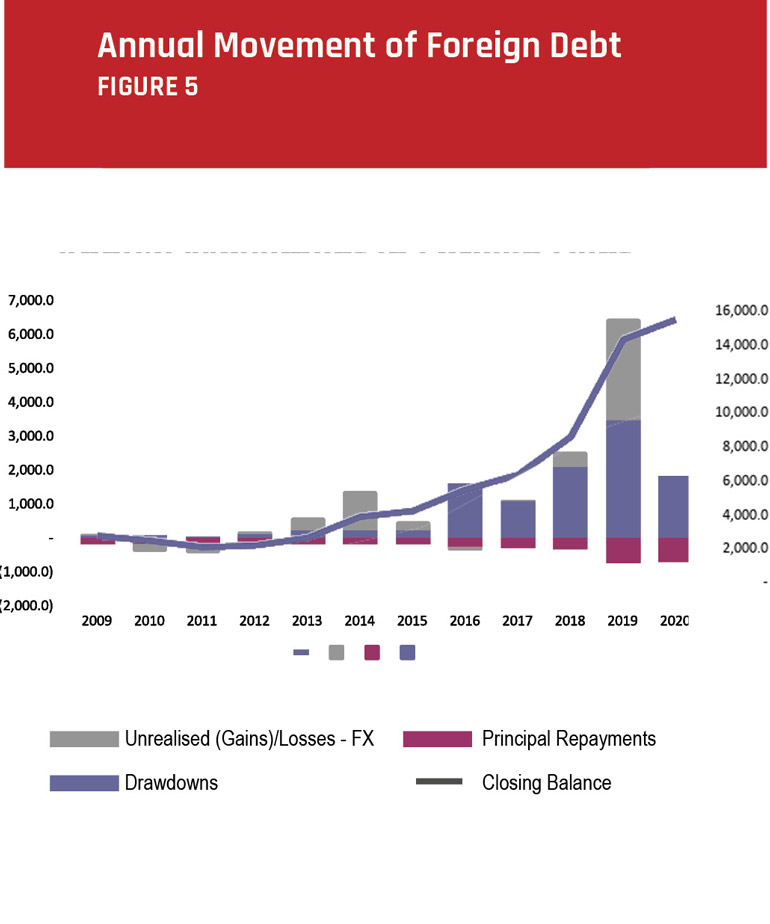

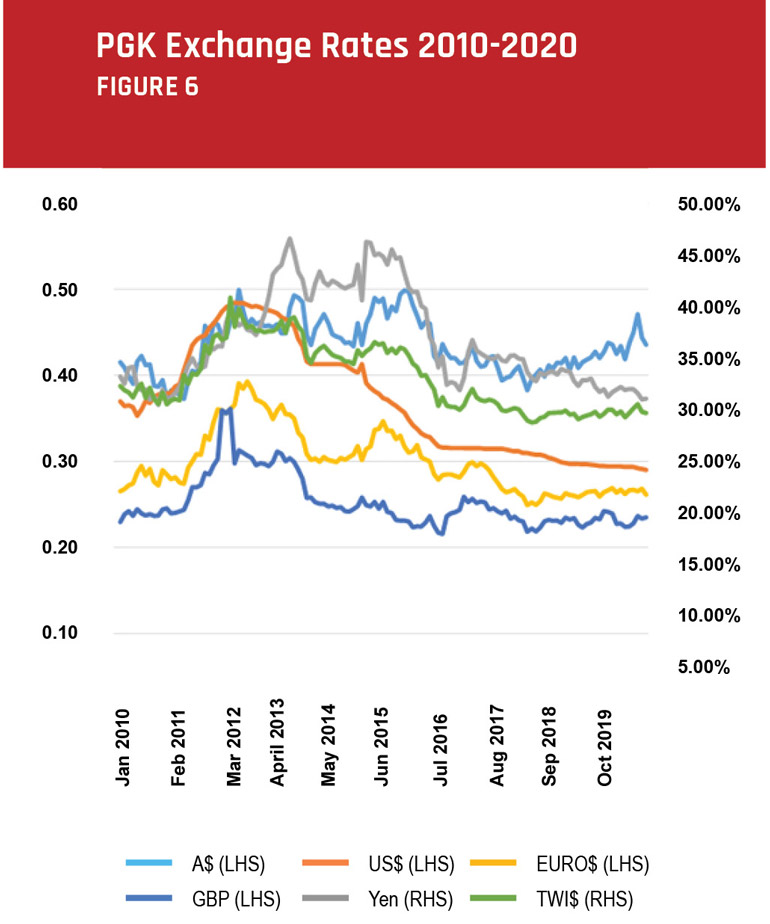

As noted above, we must also be careful not to binge on foreign currency debt since it introduces additional risks into our refinancing profile.

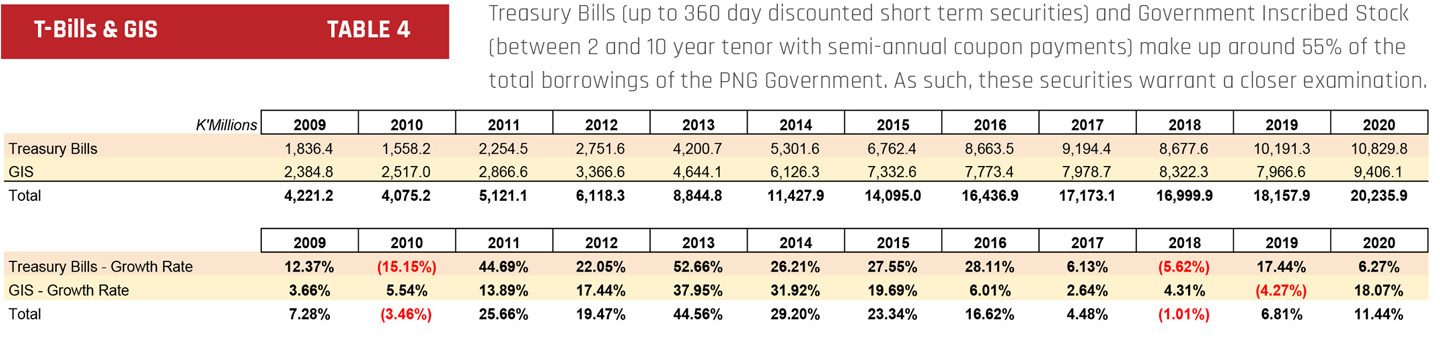

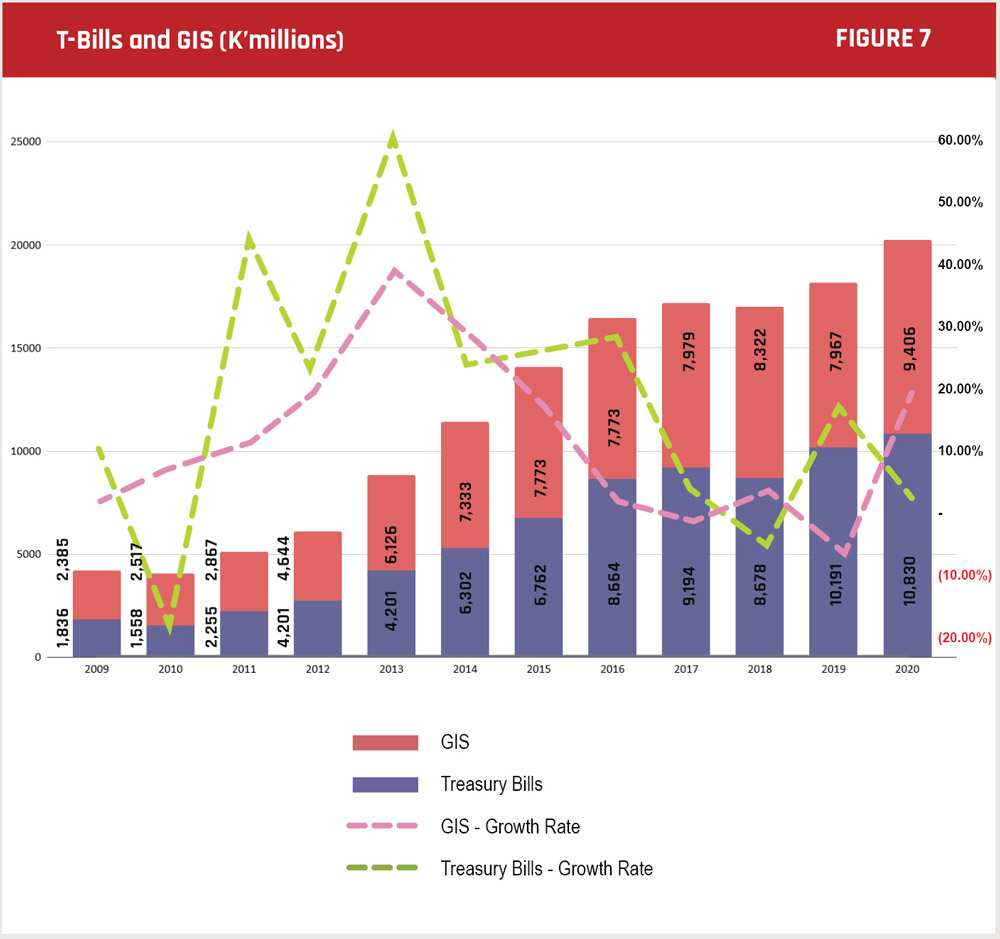

Take the banking industry for example. We saw earlier that the commercial deposit taking institutions make up a significant share of lenders in the T-bill/GIS space. Let us examine this in a bit more detail.