27 March, 2023

Welcome to this week’s JMP Report

Last week we saw 6 stocks trade on the local bourse, BSP, KSL, STO, KAM,CCP and CPL . BSP traded 1,236 shares closing 10t higher at K12.60, KSL saw 564,259 shares, trading 1t higher closing at K2.50. STO traded 2,696 shares, closing 1t higher at K19.10, KAM traded 5,559 shares, closing 15t at K0.80, CCP traded 1,273 shares, closing higher by 10 toea at K2.00 and CPL traded 45,638 shares closing steady at K0.95.

Refer details below

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT | 20 March, 2023 – 24 March, 2023

| STOCK | QUANTITY | CLOSING PRICE | CHANGE | % CHANGE | 2021 FINAL DIV | 2021 INTERIM | YIELD % | EX-DATE | RECORD DATE | PAYMENT DATE | DRP | MARKET CAP |

| BSP | 1,236 | 12.60 | 0.1 | 0.79 | K1.4000 | – | 13.53 | THUR 9 MAR 2023 | FRI 10 MAR 2023 | FRI 21 APR 2023 | NO | 5,317,971,001 |

| KSL | 564,259 | 2.50 | 0.01 | 0.40 | K0.1610 | – | 9.93 | FRI 3 MAR 2023 | MON 6 MAR 2023 | TUE 11 APR 2023 | NO | 64,817,259 |

| STO | 2,696 | 19.10 | 0.01 | 0.05 | K0.5310 | – | 2.96 | MON 27 FEB 2023 | TUE 28 FEB 2023 | WED 29 MAR 2023 | YES | – |

| KAM | 55,559 | 0.80 | -0.15 | -18.75 | – | – | – | – | – | – | YES | 49,891,306 |

| NCM | 0 | 75.00 | – | – | USD$1.23 | – | – | FRI 24 FEB 2023 | MON 27 FEB 23 | THU 30 MAR 23 | YES | 33,774,150 |

| NGP | 0 | 0.69 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 32,123,490 |

| CCP | 1,273 | 2.00 | 0.1 | 5.00 | K0.225 | – | 6.19 | FRI 24 MAR 2023 | WED 29 MAR 2023 | FRI 5 MAR 2023 | YES | 569,672,964 |

| CPL | 45,638 | 0.95 | – | – | K0.05 | – |

4.20 |

WED 22 MAR 2023 | MON 1 MAY 2023 | THU 30 MAR 2023 | – | 195,964,015 |

Order Book

We are nett buyers of BSP and KSL

Dual Listed Stocks PNGX/ASX

BFL – 4.77 –3c

KSL – . + 72 -1c

NCM – 26.27 +2.06

STO – 6.85 -8c

Alternatives

Gold 1976 -.15%

Oil – 69.16 +2.24

Silver 23.07 +2.34

Bitcoin – 27,838 +.56

Ethereum – 1762 -.82

PAX Gold – 1987 +.73

Interest rates

The TBill auction was relatively stable in last week’s auction with the 364 TBill average at 2.81%. The Bank of PNG issued a further 80mill but left the market oversubscribed by 90mill. The finance company money is offered around the 2’s with CCP being the highest. There has been no indication from BPNG on the 2023 GIS Program.

What we’ve been reading this week

Investing to make the world a better place

Tony Featherstone

Led by women in management teams and Boards, these LICs are having a positive social impact through charity, diversity, and corporate governance.

Key points

- Philanthropy has become a growing focus of the LIC sector in the past decade with some LICs providing financial and social returns.

- LIC governance is an important – and sometimes overlooked – benefit of the LIC structure for shareholders.

- This article interviews three women leading or governing LICs.

Discussions about innovation in investment products usually focus on the latest unit trust or Exchange Traded Fund. Rarely are Listed Investment Companies (LICs) considered innovators in investment and social returns.

That is no surprise. The LIC market is often perceived as a place for conservative investors seeking franked dividends. Some LICs have existed for almost 100 years, reinforcing the stereotype of an older sector run by mostly male fund managers.

Look through the 91 LICs on ASX and a different picture emerges. One where some LICs are providing tens of millions of dollars of support for Australia’s not-for-profit sector and innovating how the financial services industry approaches philanthropy.

Accompanying this LIC innovation is greater diversity in the sector. More women are managing the underlying funds of LICs, running LICs or serving on their Boards.

Make no mistake: much more diversity is needed in the LIC sector, and financial services generally. Men still dominate the LIC sector. LIC Boards – like those in other sectors – would benefit from greater gender, cultural and skills diversity.

Improving gender diversity is a focus for the funds-management industry, including for asset managers who provide exposure to their fund through an LIC, according to the 2022 Financial Services Council (FSC) Diversity Survey.

About a quarter of investment teams comprise women and gender change is heading in the right direction, the survey found. But women remain “under-represented in asset-management roles” and “driving change will take time”, said the FSC.

The need for greater gender diversity in financial services is not just about improving decision-making, organisation culture and fairness. As more women invest in listed securities – directly or through a fund or LIC – greater diversity is needed. More women running LICs and other funds reflect a growing number of female investors.

Women comprised 45% of people who began investing in ASX-listed investments, according to the ASX Australian Investor Study 2020. Just over half of all intending investors are women and many of them are younger, the ASX study found.

Innovation in philanthropy

Caroline Gurney is part of a new generation of female leaders in Australia’s LIC sector. Gurney is CEO of Future Generation, a ground-breaking asset manager that seeks to provide investment and social returns through two LICs on ASX: Future Generation Australia Investment Company (ASX: FGX) and Future Generation Global Investment Company (ASX: FGG).

Between them, the two LICs have delivered social investment of more than $65 million to charities that focus on children and youth risk, since their respective launches in 2014 and 2015 on ASX.

Twenty-four charities – and the many young people they help in cities and remote areas – benefit from Future Generation’s support.

Gurney was appointed Future Generation CEO in September 2021, having previously served on its Board. She is building on the work of Future Generation’s inaugural CEO, Louise Walsh, and its interim CEO and director, Kate Thorley (CEO of Wilson Asset Management).

“The opportunity to lead an organisation that delivers investment returns for shareholders and social returns for the community was attractive,” says Gurney. “Future Generation was the first philanthropic model of its kind in Australia. It benefits from the support of many people in our industry who provide their services on a pro-bono basis.”

The two Future Generation LICs are a “fund of funds”. Through a single investment vehicle, shareholders gain access to a portfolio that comprises more than two dozen fund managers across the two LICs.

Many of Australia’s largest and most successful asset managers manage money for Future Generation without charging annual or performance fees. In turn, Future Generation invests 1% of its assets annually with its social-impact partners.

“Through Future Generation’s LICs, shareholders get access to some of Australia’s greatest investors,” says Gurney. “Our LICs also benefit from having very experienced external people on our investment committee and across other aspects of the business. We continue to get great support from our industry. People can see our model works.”

Future Generation was conceived by Geoff Wilson AO, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer of Wilson Asset Management. His firm is a prominent manager of LICs and Wilson is a long-time advocate of the benefits of the LIC structure.

Another LIC, Hearts and Minds Investments (ASX: HM1) was established in November 2018 to provide exposure to a concentrated portfolio of equities and support Australian medical-research institutes. HM1 expands the philanthropic vision of the Sohn Hearts and Minds Investment Leaders conference, a premier investment event each year. HM1 has so far donated almost $34 million to medical research.

Understanding LICs

LICs are ASX-listed companies that manage funds that invest in Australian or global shares, or other asset classes. Like other listed companies, LICs have a Board and are subject to ASX Listing Rules and continuous disclosure requirements.

Unlike unit trusts and exchange traded funds, LICs are closed-end funds. They have a set amount of capital to invest (which changes with capital raisings). Unlike open-end funds, LIC managers do not have to worry about fund inflows and outflows.

Gurney says the closed-end LIC structure suits philanthropy. “As a company, LICs have the capacity to smooth dividend payments and utilise franking credits from their retained earnings. It’s important that Future Generation provides consistent support for our NFP partners, so they know they have the funds they need to do their work each year.”

The LIC sector’s dividend focus was another attraction for Gurney, who spent almost 18 years at UBS, an investment bank, before becoming CEO of Future Gen.

“For me, investing is all about capital growth and generating a steady stream of franked dividends over the long term.”

Gurney has so far loved her role at Future Generation. She spends much of her time talking to shareholders, meeting with the firm’s investment committee and external asset managers, and understanding the work of its social-impact partners.

More than 170 NFPs made an expression of interest when Future Generation announced last year that it was extending its support. The firm assessed every application, developed and met with a shortlist of 40 charities, and eventually narrowed it to 14.

“Future Generation has a fantastic Social Impact Manager (Emily Fuller),” says Gurney. “In the next few years, we want to do more work to quantify the social return from Future Generation’s investments and report and track that return for our shareholders.”

Gurney’s other passion is seeing more women join the LIC sector and financial services industry. She was among the few female Managing Directors at UBS, held senior roles at other global investment banks, and has served on a few NFP boards.

“We need to raise awareness of career and governance opportunities for women in the LIC sector. It’s a great area to work in and the LIC structure is ideal for long-term capital growth, philanthropy as well as other initiatives. There are many good people in our industry and, in the case of Future Generation, a lot of excellent work from many people to build on.”

LIC governance

As Gurney makes her mark in LIC executive leadership, other women are contributing to the sector as Chairpersons and non-executive directors of LIC boards.

Margaret Towers chairs Platinum Capital (ASX: PMC), an LIC on ASX that provides exposure to the global equities strategy of Platinum Asset Management (ASX: PTM). She also chairs Platinum Asia Investments (ASX: PAI), an LIC that provides exposure to Platinum’s Asian strategy.

Towers is among Australia’s most experienced directors in financial services, having worked in the industry for 35 years. An accountant by profession, Towers specialised in risk management in investment banking and wealth management.

She joined the Platinum Asset Management Board in 2007 and served on it for nine years. In March 2018, Towers joined the Platinum Capital and Platinum Asia Investments Boards as a non-executive director and Chair.

She says an LIC Board’s role is mostly about compliance and governance. “When people invest in an LIC, they are essentially buying the fund manager behind that LIC. The Board’s job is to ensure the LIC manager invests in a way that is ‘true to label’, and that the LIC always acts in the best interests of the LIC’s shareholders.”

Dividends are a focus of LIC boards, says Towers. “Many people invest in LICs for franked dividends. The LIC Board determines how those dividends are distributed and how we can [seek to] smooth income returns for investors over longer periods.”

Capital management is another consideration for LIC Boards. LICs that trade at a persistently large discount to their Net Tangible Assets (NTA) frustrate shareholders and can trigger closure or takeovers as stronger LICs acquire underperforming competitors.

Simply put, the LIC’s share price is less than the value of its underlying investments – thus the discount. Some investors argue that buying $1 worth of assets (the NTA) for, say, 80 cents (the share price) is an opportunity. But some LICs struggle to narrow the gap to their NTA because the market doubts their performance, personnel or dividend record. The discount can widen when the asset class the LIC invests in is out of favour or less liquid.

For LIC Boards, this means finding ways to reduce the discount to NTA and ideally trade at a slight premium to NTA. This could involve an on-market share buyback (as Platinum Capital and Platinum Asia have in place), although these have proven to have limited success. Alternatively, the LIC can strive for greater promotion among analysts and investors, to improve its share liquidity.

Capital raisings add other challenges for LIC Boards. Raise capital when the LIC trades at a large discount and existing shareholders can be diluted, depending on the instrument used. Raise capital when the LIC trades at a large premium and new investors overpay for assets.

Knowing if and when to wind up an underperforming LIC and return funds to shareholders is another LIC Board task.

Towers says this layer of governance from LIC Boards is valuable for investors. “I firmly believe every listed or unlisted entity that takes money from investors needs strong governance and oversight. There’s huge value in having an independent Board overseeing the LIC and ensuring all its shareholders are treated equally.”

Driving good governance

Joanne Jefferies is General Counsel and Group Company Secretary at Platinum Asset Management, Platinum Capital and Platinum Asia Investments.

The role of the company secretary has evolved significantly over the years. Although traditionally responsible for coordinating Board meetings, papers and drafting minutes, company secretaries these days are expected to advise Boards and implement good corporate governance practices. Being officers, company secretaries also have certain statutory responsibilities.

Jefferies, a lawyer and corporate-governance expert, has worked in the financial services industry in several countries over the past 27 years. She joined Platinum in 2016 and liaises with Towers and other directors on Platinum’s LIC Boards.

She says LIC directors need a high level of financial literacy. “LIC boards spend a lot of time looking at investment performance, dividends, franking and other capital-management issues. They need skill and experience in compliance and risk management, and a deep understanding of their duties as directors.”

Platinum’s LIC boards meet quarterly, in addition to other discussions outside the Board-meeting cycle. “Regardless of the size of company, there’s a significant amount of work involved in being on a LIC Board,” says Jefferies. “In the LIC sector, there is a lot of money being invested on behalf of shareholders. As corporate entities, LICs are subject to the provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 and being listed on the share market adds another dimension in terms of the ASX Listing Rules.”

Jefferies would like to see more women on Boards of LICs and in the financial services sector generally. “My observation is that gender diversity in Australian financial services lags other markets, such as the UK (where Jefferies worked for 11 years). You see too many women here leave the industry to raise families and then never move on to senior executive roles or Board positions. That’s a lost opportunity.”

Jefferies favours the introduction of quotas, where financial services Boards are required to meet diversity numbers. “That’s my personal view,” she says. “We need to get more women on Boards and quotas are a way to fast-track that. Some people disagree about the need for quotas, but I see firsthand the contribution women make on Boards and how Boards generally are better off having a mix of men and women.”

Oliver’s insights – nine key lessons for today from the 1970s, 80s and 90s

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist, AMP Investments

Key points

– The experience of the high inflation 1970s and its aftermath hold key lessons for today. In particular, that once high inflation becomes entrenched in expectations that it will stay high, inflation is very hard to get back down but also that there are lags in the way monetary policy impacts.

– Whether the RBA and other central banks have done enough is a judgement call. The RBA is signalling that it has not yet done enough so more rate hikes are on the way. Our view is that the RBA has likely already done enough. Upcoming retail sales and jobs data are critical in this.

Introduction

In 1981 on a holiday with my parents to Hawaii we got into a discussion with some Americans about their new President, Ronald Reagan, and they said he had to deliver some tough economic medicine after years of policy mismanagement. At the time I dismissed them, but as the years went by I concluded that they had a point. The 1970s were an economic mess as inflation was allowed to get out of control. In fact, things were so bad that there was a wave of nostalgia for the 1950s and early 60s when things seemed a lot better – starting with American Graffiti, Happy Days, Laverne and Shirley and the rise of retro radio stations playing hits from the 50s and 60s. With inflation surging lately, what lessons can be drawn from the 1970s and its aftermath in terms of today’s problems. This is important because if we don’t learn the lessons of the past, we are bound to repeat them. This is particularly pertinent now as I often hear the comment “why are we so worried about a bit of inflation?” and “why is the RBA inflicting so much pain?”

What went wrong in the 1970s?

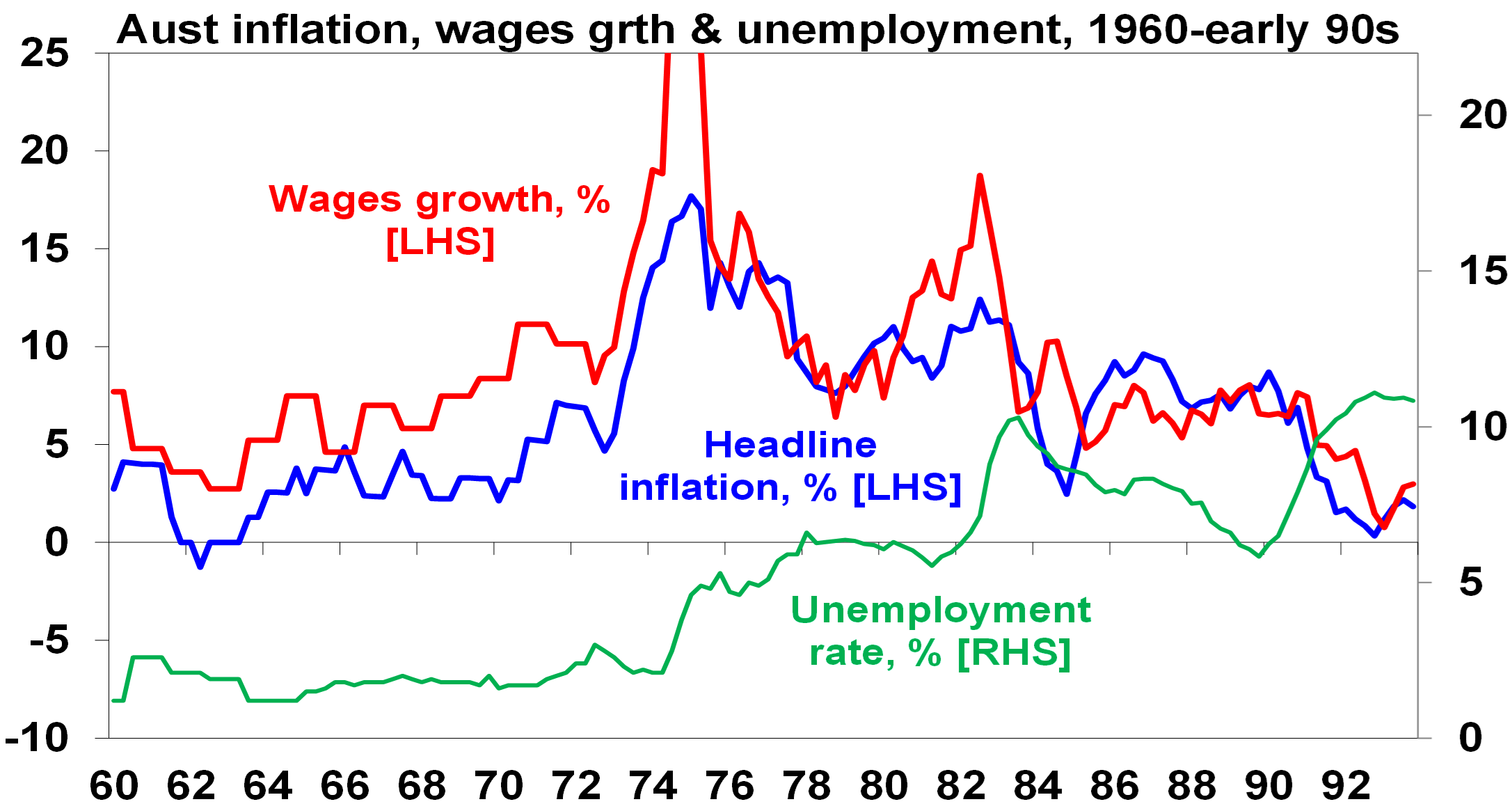

But first it’s worth a brief recap. From around the mid-1960s inflation started rising. First in the US and then in Australia. It was driven by a combination of tight labour markets, more militant workers demanding higher wages, a big expansion in the size of government, disruption from the Vietnam War, easy monetary policies, social unrest and years of industry protection reducing competition and pushing up prices. It really blew out after the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 and the second oil shock after the Iranian revolution of 1979. The surge in inflation came in waves, reaching double digit levels. It also combined with frequent recessions as policy makers tightened monetary policy in response to high inflation but were too quick to ease when growth slumped only to see inflation take off again driving more tightening and another economic downturn. The end result was a decade of high inflation, high unemployment and slow economic growth from which it took a long time to recover. For investors it was bad as high inflation meant high interest rates, high economic volatility & uncertainty and reduced earnings quality all of which demanded higher risk premiums to invest (& low PEs). The 1970s were one of the few decades to see poor real returns from both shares and bonds.

Source: ABS, AMP

So what broke it?

The malaise ultimately ended after voters turned to economically rationalist political leaders – like Thatcher, Reagan and Hawke and Keating in Australia. The policy response involved:

- tight monetary policy which drove severe recessions, ultimately culminating in inflation targeting;

- supply side reforms like deregulation, privatisation & competition laws to make it easier for the economy to meet demand;

- this was aided by globalisation and then in the late 1990s the tech boom – which boosted the supply of low-cost goods and services;

- in Australia, the prices and incomes Accord between Government, unions and business helped break the wage price spiral at the time.

This all broke the back of inflation with some in the 2000s calling it dead.

Key lessons

There are several lessons from the malaise of the 1970s and its aftermath and early 1990s recession in Australia for the inflation problem of today:

- What won’t work. First, the experience of the 1970s and 1980s provides a clear list of things that won’t work to solve the problem:

- Higher wage growth to keep up with inflation – this just perpetuates high inflation making it harder to get back down.

- Price controls – these were tried, eg, in the early 1970s in the US. But they restrict supply and when removed inflation was worse than ever.

- Replacing the RBA Governor – doing this mid-way through the problem would risk shaking confidence in the RBA’s anti-inflation commitment at the worst time likely resulting in even higher interest rates. The US saw something similar in the 1970s when it replaced William Martin at the Fed with Arthur Burns which just perpetuated high inflation.

- Raise the RBA’s inflation target – this would also reduce confidence in its ability to get inflation down and mean higher interest rates.

- Shift responsibility for inflation control back to government – this sounds fine in theory as governments have more levers to pull (eg it could impose a 1% temporary income tax surcharge to cool demand which would spread the load more fairly beyond those with a mortgage). But unfortunately, politicians have shown an inability to inflict the pain necessary to slow inflation. So, it doesn’t work in practice. It was the way things were done in Australia in the 1970s and its failure led to the widespread adoption of central bank independence focussed on meeting an inflation target.

- Containing inflation expectations is key. Once inflation takes hold it gets harder to squeeze out. This relates to “inflation expectations”. Once inflation has been high for a while consumers and businesses expect it to stay high and so behave in ways – via wage demands, price setting and acceptance of price rises – that perpetuate it. A wage price spiral is a classic example of this where prices surge, workers demand wage rises to compensate which boosts costs & drives a new round of sharp price rises. This is an example of the “fallacy of composition” – while it is rational for an individual to demand a wage rise to match inflation if all workers do so it just leads to a further surge in prices.

- Whether its supply or demand, central banks have to respond. While the initial impetus to a surge in inflation may be constrained supply if it occurs when demand is strong or goes on for too long, central banks still have to respond to cool demand and signal they are serious about containing inflation. Central banks failure to do this after the 1973 OPEC oil shock contributed to inflation getting entrenched in the 70s.

- Avoid stop go monetary policy. There is a danger in easing monetary policy too early in a downturn if inflation expectations have not been tamed. This occurred in the 1970s with inflation slowing and central banks easing as growth slowed but inflation soon rising even higher. This underpins talk central banks will keep rates “higher for longer”.

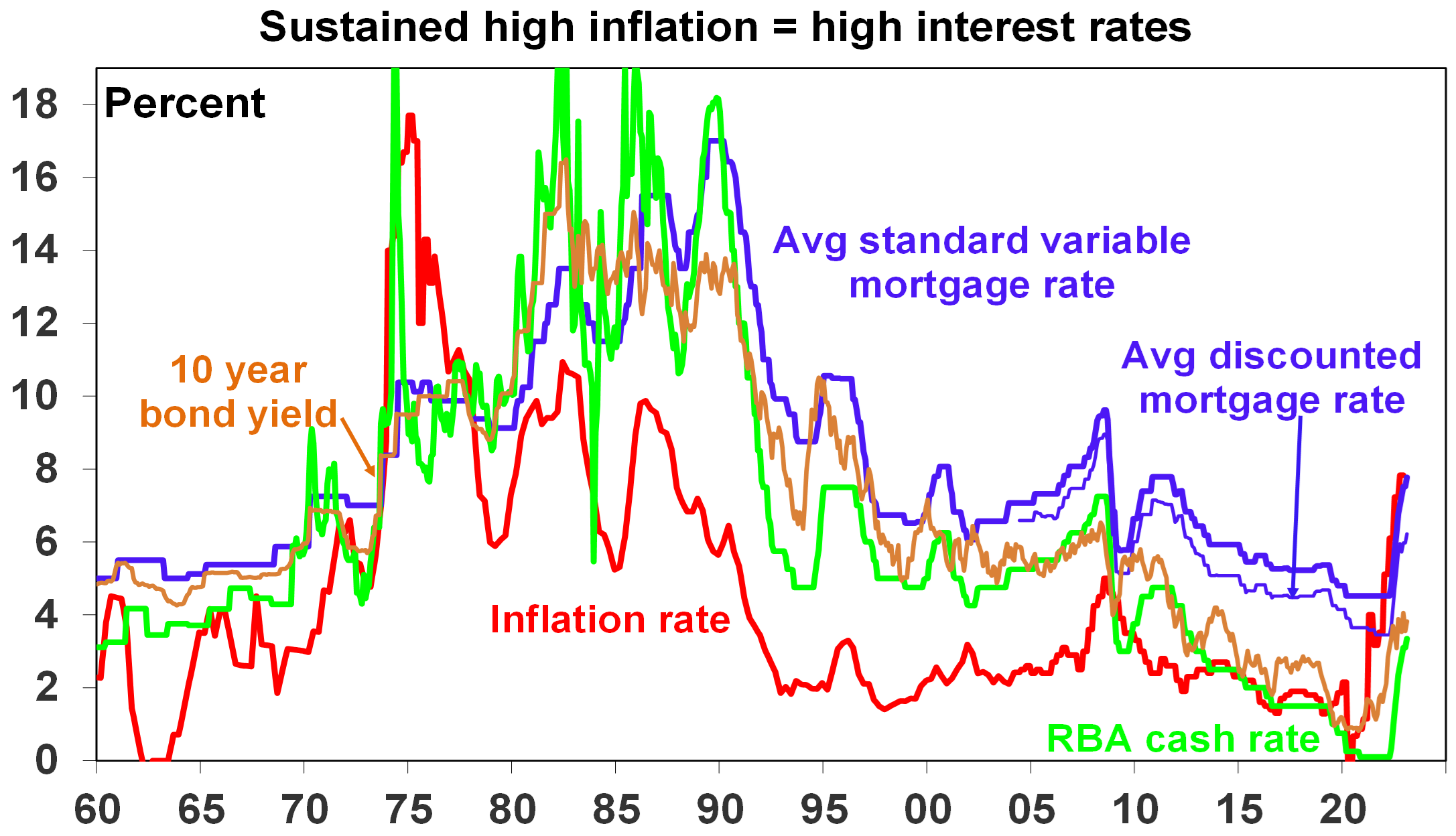

- Entrenched high inflation will mean entrenched high interest rates. This is because investors will start to demand compensation for the fall in the real value of their savings by demanding higher rates. So interest rates rose through the 1970s into the 1980s. And this of course weighs on the valuation of shares and property. 10-year bond yields of around 3.5% to 4% are fine if investors expect inflation will fall to say 2-3% but if they believe inflation will stay high at 6-8% then they are too low.

Source: ABS, AMP

- Entrenched high inflation is bad for the economy. Because it distorts economic decisions it can cut economic growth as in the 1970s, add to economic uncertainty which hampers investment & boost inequality.

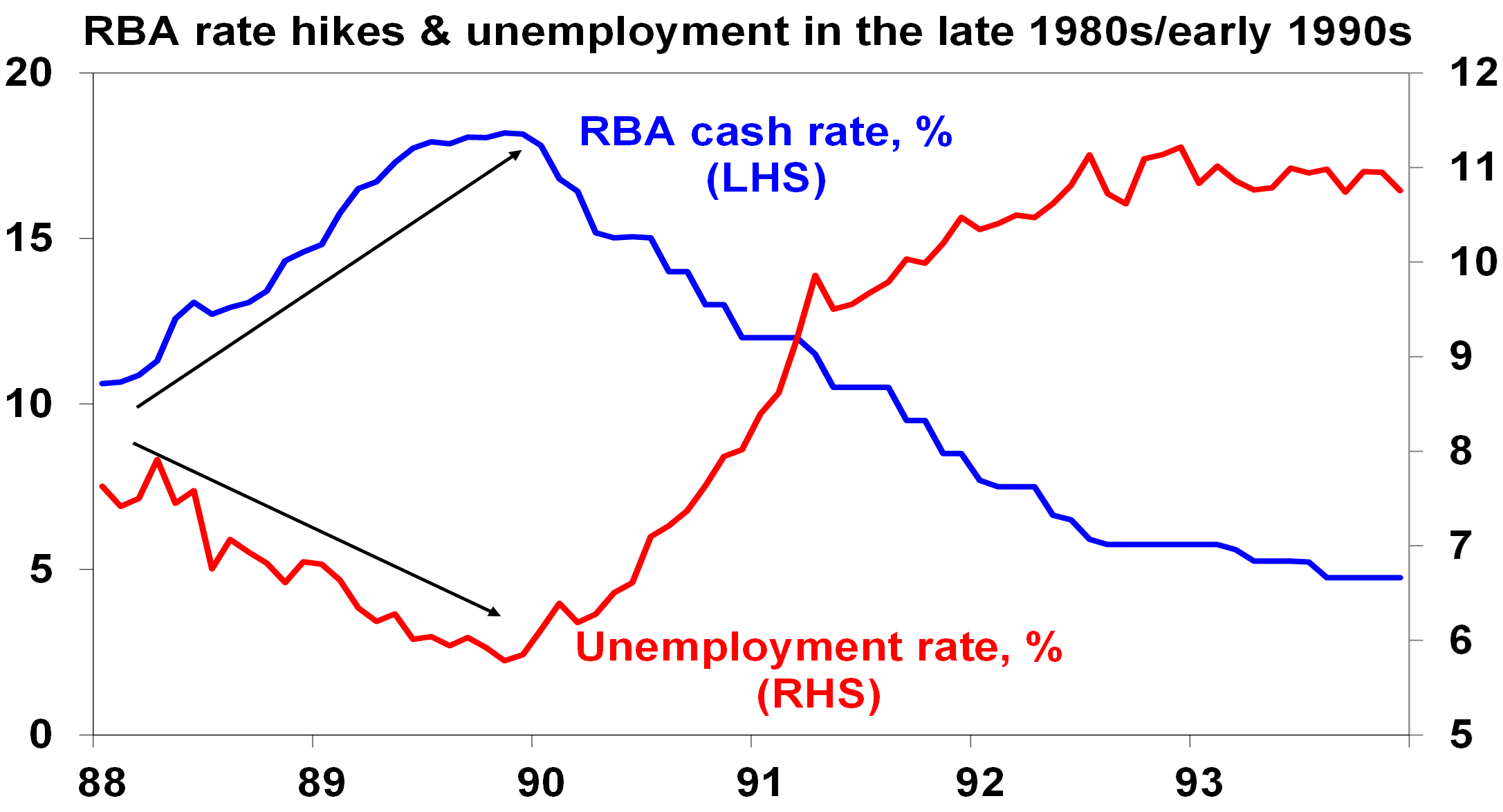

- Once entrenched high inflation risks requiring a deep recession to remove it. This was seen in the deep recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s in Australia which saw double digit unemployment. This was because by the late 1970s inflation expectations in the US as measured by the University of Michigan consumer survey were running around 10% following years of very high inflation making it harder to get inflation down. Australia was likely similar.

- Governments should focus on the supply side. The practical inability of governments to adjust fiscal policy much to control inflation means the best it can do in the short term is not add to the problem and this means reducing budget deficits and limiting new spending. Longer term there is a lot that government can do to help control inflation and its all about supply side reform to make the economy work more smoothly, ie deregulate, cut back government and competition reforms. Unfortunately, the political appetite for such reforms is low.

- Monetary policy operates with a lag. The early 1990s recession showed monetary policy works with a lag. This seems contradictory to the fourth point above but highlights the risk of overtightening. The lags arise as it takes time for rate hikes to be passed on to borrowers, that to slow spending and then for slower demand to lead to less employment and the flow on of this back to households and for all of this to cool inflation. This can take 12 months or more. So just looking at inflation and jobs data can be misleading as they are lagging indicators. In the late 1980s the RBA kept hiking and unemployment kept falling. But by early 1990 it was clear it had gone too far.

Source: ABS, RBA, AMP

Source: ABS, RBA, AMP

So what does it all mean for today?

The good news is that this is not 1980 and more like the early 1970s: inflation expectations are low; there is no evidence of a wage price spiral, notably in Australia; supply bottlenecks, freight costs and surging money supply which led inflation are now reversing; and high household debt ratios compared to the 1970s should make monetary policy more potent. But the lessons from the 1970s explain why central banks are so fearful of letting inflation get out of control and also the difficult balancing act facing them. As RBA Governor Lowe said they “are managing two risks…not doing enough [resulting in high inflation persisting & proving costly later] [and] that we move too fast, or too far” and trigger recession. Balancing these two risks is seen as resulting in a narrow path to low inflation and the economy continuing to grow. But what is too much or too little tightening is a judgement call. The RBA’s view has become more hawkish after the December quarter CPI and is signalling at least two more rate hikes and money markets and the consensus of economists have moved to reflect this with consensus rate expectations rising above 4%. Our view is that the RBA risks doing too much given the high vulnerability of a significant minority of indebted Australian households and that the impact of past rate hikes is just being masked by normal lags accentuated by revenge spending associated with reopening. Signs of slowing consumer spending and jobs growth along with there still being no evidence of a wages breakout in Australia are consistent with this. As such, it risks a re-run of the late 1980s/early 1990s experience where Australia was inadvertently knocked into a deep recession as the lagged impact of rate hikes took time to show up. So, while we believe rates are close to the top, the RBA’s tough guidance means that the risks are skewed to the upside. Further evidence of a slowing consumer and jobs data are necessary to cause the RBA to rethink so upcoming retail sales and jobs data are critical in this.

YOU NEED TO UNDERSTAND THIS – ITS ALL ABOUT LIQUIDITY

Posted | 27/03/2023

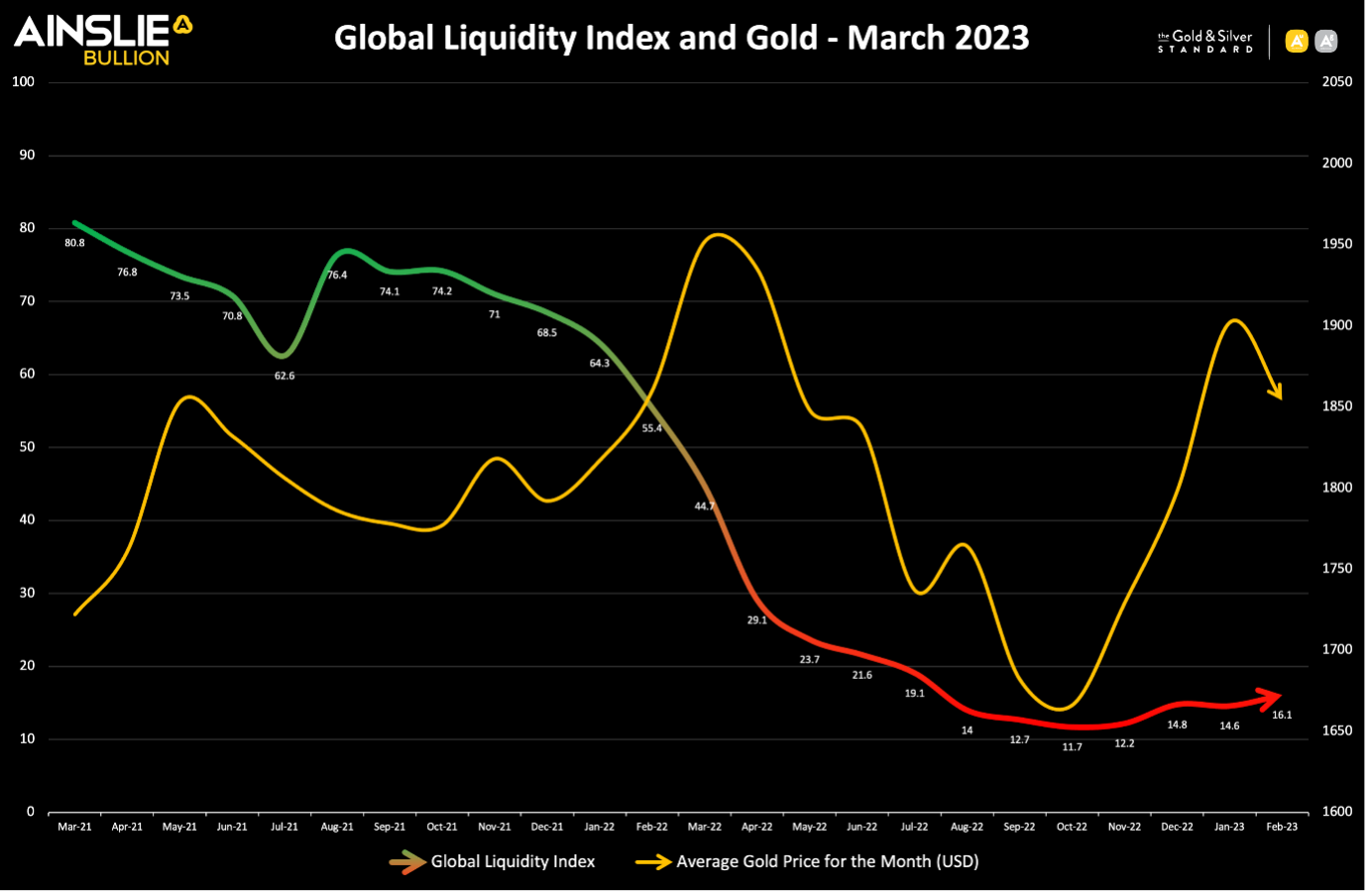

Friday night saw more banking dramas amid Euro banks with none other than Deutsche Bank yet again hogging the headlines, down 14% at one point before finishing down 8% in one session. DB also saw its CDS’s surge as investors scrambled into protection (that someone has the other side to don’t forget!). A few weeks ago, before any talk of banking crises, we wrote the possibly prophetic article titled ‘SPLASH’ LANDING – WHY LIQUIDITY IS ALL THAT MATTERS & GREAT FOR GOLD and spoke to it further in the Insights interview that afternoon. In hindsight and as we suggested then, these are critically important concepts to understand as you choose investments to protect and grow your wealth amid the financial chaos hidden from plain view and most people’s understanding.

Anyone watching the financial twitter-verse will have seen the following chart that fits well into the above. Amid everyone’s fixation on whether the Fed will or will not raise rates and stop Quantitative Tightening (QT), this happened since SVB was bailed out…

And so debate rages over whether that was QE or not. Frankly it doesn’t matter. What it signifies very very clearly, is the Fed has turned on the liquidity spigots to stabilise the banking situation. Whether its traditional QE (printing money to buy bonds) or, as appears to be the case here where they are ‘lending’ newly created money to banks with their (underwater) bonds provided as collateral (so as not to trigger the mark to market losses should they actually sell them); the end result is a whole lot of new money pouring into the system to buy financial assets given banks can’t give you any interest because the yield curve is inverted. That is not to mention how safe you feel with your cash in one at the moment too… Can kicked down the road again… Nothing to see here….

We referred to Cross Border Capital’s Michael Howell in the abovementioned Ainslie article. He spoke insightfully to all this recently as follows:

“When banks lose deposits it results in a tightening of liquidity conditions. Using the US as the example, the research based assumption has been that the minimum operating level of bank reserves was in the order of $2.5 trillion. Bank reserves have been sitting very close to that minimum number for quite a while now. The events of the past couple of weeks have shown that the level before things break is now likely closer to $3 trillion (which also makes sense that this number rises over time as global debt has also risen over time).

The problem is that once you get a crisis the demand for reserves goes up so in actual fact that $3t number is currently rising and the level of reserves required in the system now is probably closer to $3.5 trillion. So what we’re looking at here is potentially a a significant increase in the size of the FED balance sheet to plug the hole.

We can argue all day whether it is technically QE or not, but whichever way you look at it it’s a liquidity easing because the Federal Reserve has no other choice than to backstop the system (which so far they have done very quickly and effectively the moment any real stress is identified).

This ultimately results in monetary inflation and the best instrument that hedges against monetary inflation is gold because gold has been long-standing as a monetary inflation hedge. There is a subtle but very important distinction between a monetary inflation hedge and a High Street inflation hedge and gold is not always a great High Street inflation hedge but it’s always been a very good monetary inflation hedge. The new version of a monetary inflation hedge is Bitcoin. Gold and Bitcoin are likely to be pretty decent measures of liquidity (they have a very high correlation to liquidity movements and act as a “barometer” of liquidity) so if liquidity goes up you could expect a significant step move higher in Gold and BTC.”

The following charts spell this out very clearly (albeit the gold one hasn’t captured the rally on Friday back up to near $2,000):

You will see above that gold broke that correlation for a while in early 2022 as its other role, that of safe haven asset, was bid during the Ukraine invasion. That invasion never escalated to the point the market feared (yet) and it revisited its trend down in line with liquidity.

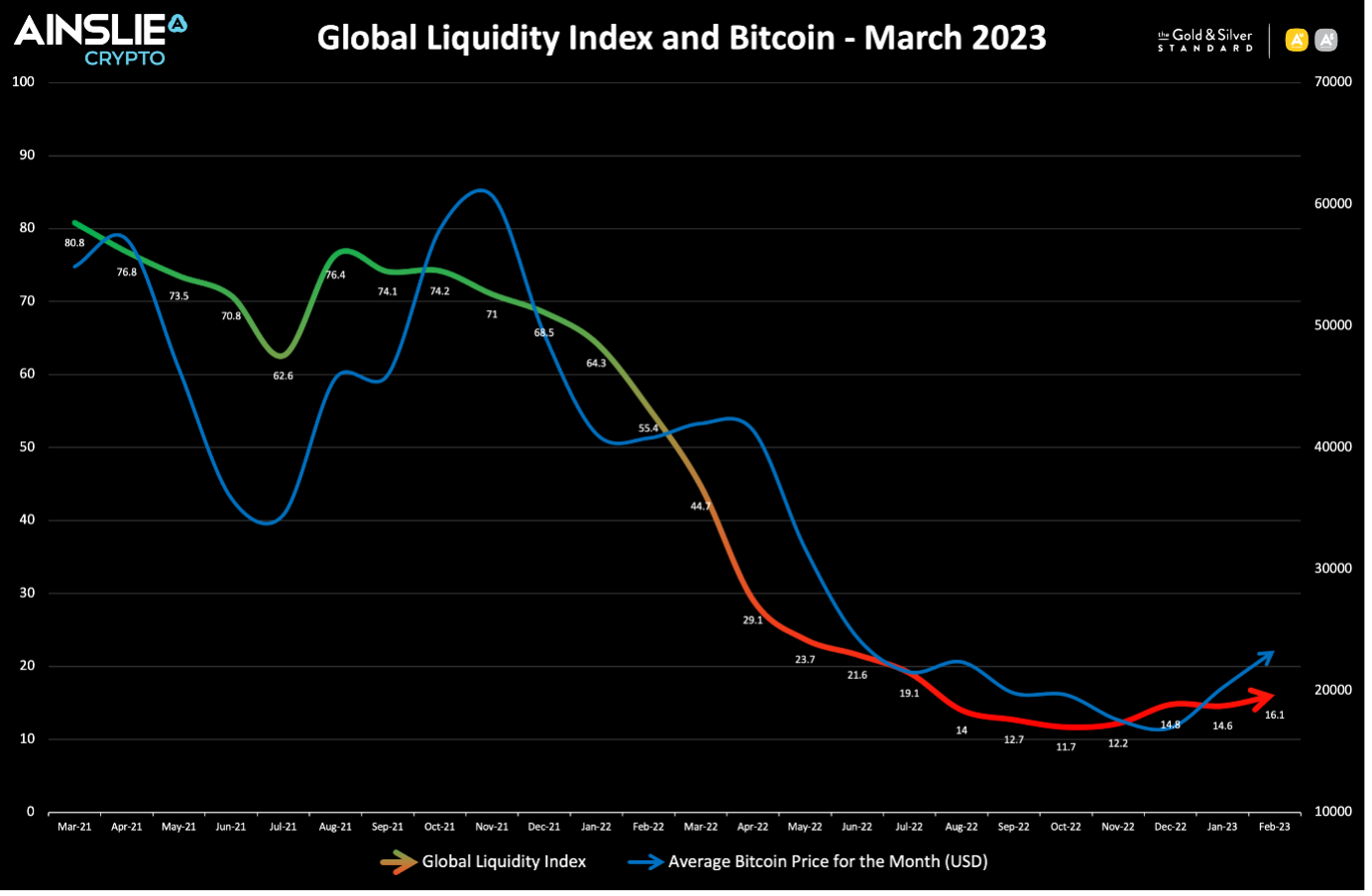

As he said too, BTC follows it more closely than any other asset and it never got the Ukraine bid:

The correlation, regardless, is undeniable. The logic behind it, likewise, undeniable. As more and more ‘money’ is created and injected into the system, the more real money (unable to be simply printed or created) is the logical home for it.

The global liquidity cycle is exactly that, a cycle. It somewhat predictably has 3.5 years up, 3.5 years down. Howell says it bottomed last October. Gold and bitcoin agree. If history repeats, as it has done for decades, then we have a 3 year bull market ahead of us.

Article care of Ainslie Bullion

I hope you have enjoyed this week’s read. If you would like to discuss with me on how to open a new account and how you go about trading on the Stock Exchange, please feel free to reach out.

Regards,

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

Level 1, Harbourside West, Stanley Esplanade

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814