6 May, 2024

Hello and welcome to this week’s JMP Report,

On the equity front last week we saw 3 stocks trade on the local market. BSP traded 16,976 shares closing 46t higher at K16.76, KSL traded 467,448, closing 3t lower at K2.92 and CCP traded 784 shares, closing 1t higher at K2.16.

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT | 29 April, 2024 – 3 May, 2024

| STOCK | QUANTITY | CLOSING PRICE | BID | OFFER | CHANGE | % CHANGE | 2023 INTERIM | 2023 FINAL DIV | YIELD % | EX-DATE | RECORD DATE | PAYMENT DATE | DRP |

| BSP | 16,976 | 16.76 | 16.75 | – | 0.46 | 2.74 | K0.370 | K1.060 | 8.87 | TUE 27 FEB 2024 | WED 28 FEB 2024 | FRI 22 MAR 2024 | NO |

| KSL | 467,448 | 2.92 | 2.92 | 2.95 | -0.03 | -1.03 | K0.097 | K0.159 | 8.82 | TUE 4 MAR 2024 | WED 6 MAR 2024 | MON 15 APR 2024 | YES |

| STO | – | 19.37 | 19.37 | – | – | 0.00 | K0.314 | K0.660 | 5.04 | MON 26 FEB 2024 | TUE 27 FEB 2024 | TUE 26 MAR 2024 | – |

| NEM | – | 145.00 | 145.00 | – | – | 0.00 | – | USD 0.250 | 0.63 | MON 4 MAR 2024 | TUE 5 MAR 2024 | WED 27 MAR 2024 | – |

| KAM | – | 1.20 | 1.15 | – | – | 4.17 | K0.12 | – | – | – | – | – | YES |

| NGP | – | 0.69 | – | – | – | 0.00 | K0.03 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CCP | 784 | 2.16 | 2.15 | – | 0.02 | 0.93 | K0.110 | K0.131 | 6.21 | FRI 22 MAR 2024 | WED 27 MAR 2024 | FRI 19 APR 2024 | NO |

| CPL | – | 0.79 | – | 0.79 | – | – | – |

– | – |

– | – | – | – |

| SST | – | 45.00 | – | 50.00 | – | 0.00 | K0.35 | K0.60* | 1.33 | WED 24 APR 2024 | FRI 26 APR 2024 | FRI 26 JULY 2024 | NO |

Dual Listed PNGX/ASX Stocks

BFL – 5.97 +12c

KSL – 94c +1.5c

NEM – 62.02 -3.68

STO – 7.48 -24c

The week’s review on interest rates

In the short end we saw 2.35bn Central Bank Bills taken out of the banking system with CBB rates set at 2%. This is available to the professional financial institutions only. In the longer end, Bank PNG offered 171mill 364 day TBills with the bank issuing 111mill at 3.77% up 7bpts from last week after receiving a total of 180mill in bids. It appears the Bank is tightening Monetary Policy and we can expect to see rates ease further.

We understand that Bank PNG will hold the next GIS auction on the 21st of May.

Other assets we like to monitor

Gold – 2302 -$33

Silver – 26.56 -62c

Palladium – 950 -$6

Platinum – 958 +$42

Bitcoin – 63711 +0.24%

Ethereum 3,133 -5%

What we have been reading

Australia’s superannuation rules leave Pacific workers out of pocket

JESSICA COLLINS | Published 3 May 2024

More than 40,000 Pacific Islanders working in Australia are being unfairly taxed on superannuation contributions – enforced savings payments that they are already unlikely to ever claim when they return home.

Under the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme, which aims to fill labour gaps in regional Australia with Pacific workers, over a four year visa term Pacific Islanders are collectively paying at least half a billion dollars in superannuation – a total which is more than Australia’s annual bilateral aid to Papua New Guinea.

This whopping superannuation total is calculated using just the minimum wage and hours worked across nine months in each of the maximum four years of a PALM-associate visa. Given the average PALM worker is working and earning a lot more than that, the actual figure will be higher.

The government hasn’t revealed exactly how much superannuation is being collected from PALM workers in Australia and, more importantly, how much is claimed after the worker returns home.

On an estimate of the taxes paid for those who do successfully manage to return their money home, an average PALM worker in the horticulture industry would lose nearly $10,000 of their superannuation to the Australian Tax Office.

Workers returning to rural villages or far-flung islands without reliable internet and the help of Australian officials are poorly placed to navigate the mounds of paperwork necessary to claim back this portion of their hard-earned wages. To complicate matters, workers can only claim their superannuation once they leave Australia. Applicants need certified copies of identity papers, a $55 Certification of Immigration Status if they have paid more than $5,000 in superannuation, a home address, and usually an open Australian bank account – big demands on PALM workers back in the Pacific.

Claimants can also be charged a fee by the superannuation company when opting for an Australian bank deposit rather than an Australian dollar cheque, which can’t easily be banked in the Pacific. The Pacific worker must then transfer their superannuation balance from an Australian bank account to the Pacific, through one of the most expensive remitting corridors in the world.

But that’s not the only charge. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) then takes its slice. Between 35 to 45 per cent of Pacific workers’ total superannuation.

We can’t be sure exactly how much money from Pacific workers is left stranded in their superannuation funds until the government provides data. But on an estimate of the taxes paid for those who do successfully manage to return their money home, an average PALM worker in the horticulture industry would lose nearly $10,000 of their superannuation to the ATO, without benefiting from access to key services such as Medicare.

A seasonal fruit worker picks raspberries at the Pinata Farm near the Glasshouse Mountains in Wamuran, Australia (Carla Gottgens/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

These taxes are small fry for federal revenue but are a huge loss to the Pacific’s development. Taxing PALM workers at the rate of more than a third of their superannuation means less food on tables for the Pacific’s poorest. Every dollar counts in the Pacific.

If Australia wants to demonstrate its close-relationship credentials with the region, it must reform the superannuation element of the PALM scheme. By doing so the government will help to make great strides in lessening regional aid dependency – an aspiration shared by Pacific leaders.

Reform could involve portable superannuation schemes with Pacific nations, much like Australia has with New Zealand, so that PALM workers can regularly send their money home to a providence fund, alongside remittances, at low cost. It would mean no tax rate applied to the removal of superannuation from Australia to the Pacific for PALM workers – following the lead of New Zealand.

Putting the legislation in place would take work considering the differences in regulatory standards across the region. But this hasn’t stopped New Zealand, which has set up its own portability relationships with Pacific nations.

Another option is to remove the requirement for PALM workers to pay superannuation. Australia already gives this visa cohort a special tax rate of 15 per cent.

Failing this, the government could consider a central government bank account into which all PALM workers request their superannuation be deposited. Much like it already does for monthly pensions paid into overseas accounts, the Reserve Bank of Australia could then remit individual superannuation lump sums into nominated bank accounts in the region once visas expire. Again, the early withdrawal tax could be removed for PALM workers accessing their superannuation via this mechanism.

Any PALM superannuation reform must be targeted, so there will be no right of precedent claim for the remaining two-and-a-half million temporary visa holders currently in Australia that don’t share the same development situation, and strong historical and regional ties.

But by changing the superannuation arrangements for the Pacific, Canberra will demonstrate to the tens of thousands of PALM workers currently in Australia, and their families back home, that Australia supports a united Pacific family and a strong and economically resilient region.

Oliver’s insights – The art of happiness – economics and the “hedonic treadmill”

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist, AMP Investments

29 Apr 2024

Key points

– Despite a big rise in GDP per person, surveyed measures of happiness have been flat to falling in the US and Australia.

– Younger people in the US, Canada, Australia and NZ are the least happy age group. This is a major change from 20 years ago and may be due to the rise of social media.

– Some suggest we are on an “hedonic treadmill” and should focus on something like Gross National Happiness.

– Such an approach would have major implications for investors, but it’s doubtful it would improve happiness.

Introduction

On a recent road trip, I was listening to a bunch of Taylor Swift and Andy Williams’ CDs and what struck me was how different the topics of the songs were. Andy’s covers were far more upbeat (with songs like ‘Happy Heart’ and ‘For All We Know’) whereas Taylor has lots of ‘somebody done me wrong’ songs. Of course, it’s dangerous to generalise but then I saw a study from the University of Innsbruck finding that songs have become “gloomier” and “angrier” compared to 50 years ago – which made me think about what it tells us about the wider concept of happiness.

Pursuing happiness is at the centre of our existence. There’s lots of evidence happiness is good for us – happy people live longer, are healthier, more resilient, more creative, are better leaders and are more sociable. Which is where economics comes in. Despite often being portrayed as the “dismal science”, economics is in fact all about happiness. The economic problem is about how to maximise utility (or happiness) with limited resources. So, economics can be thought of as the “art of happiness”. But measures of happiness have been flat or falling in developed countries. So, what gives? Is economics failing us? This became a big issue in the 2000s with lots of books on happiness. There is now even a regular “World Happiness Report using Gallup surveys attempting to gauge happiness.

Rampant prosperity

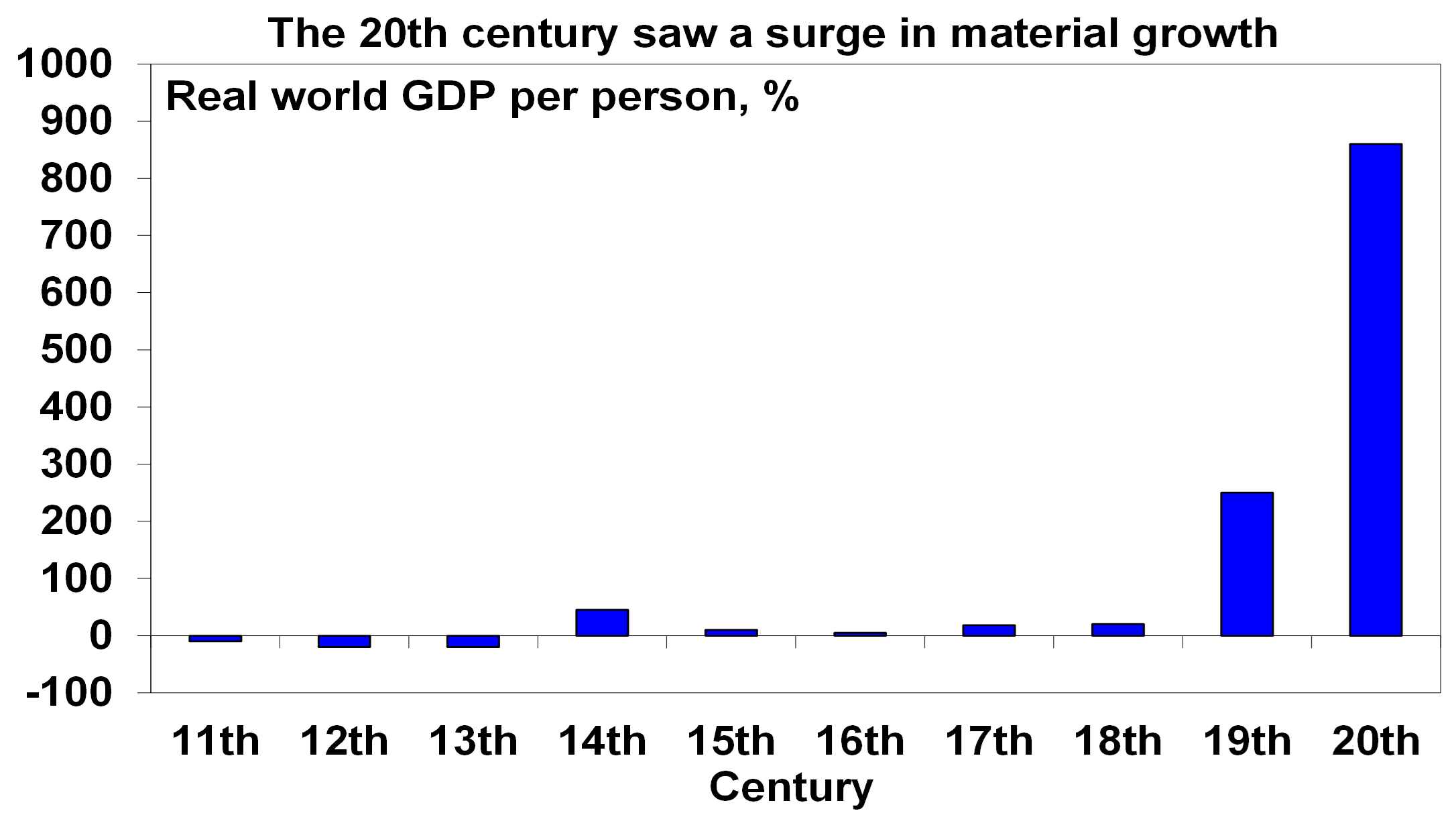

The 19th century saw the start of rapid global economic growth.

Source: Angus Maddison, AMP

This really took off in the 20th century as technological innovations such as electricity, the internal combustion engine and silicon chips came together to rapidly boost productivity. Consequently, real income or Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per person surged globally. This in turn led to a massive rise in material prosperity with, eg: large climate-controlled homes; high speed affordable travel; high quality & variety of food; a huge array of goods; a massive increase in lifespan, and instant communication & entertainment.

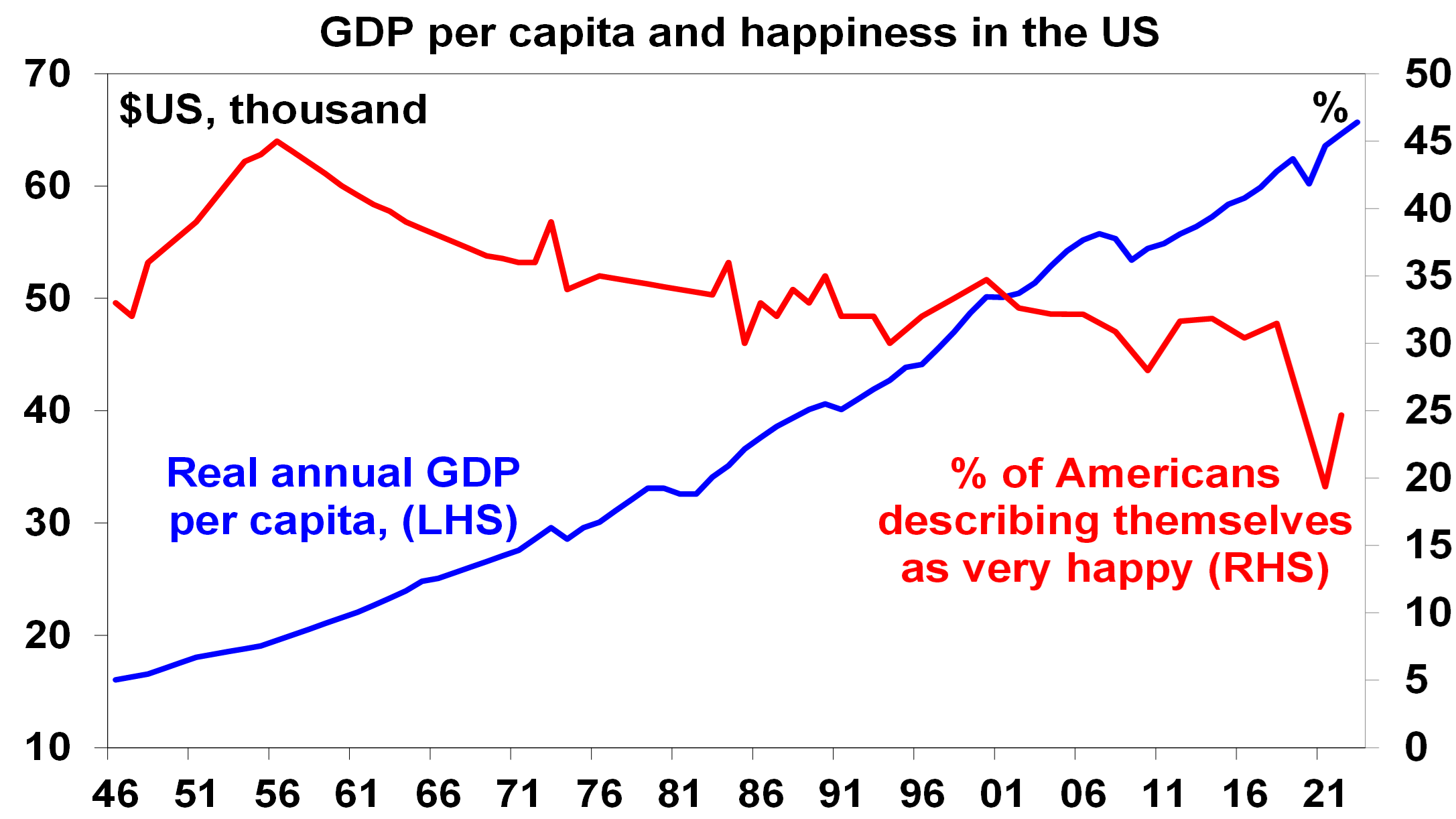

But stagnant happiness in recent decades

Despite the huge surge in material prosperity there is little evidence that happiness levels in developed countries have improved in the last fifty years. This is illustrated in the chart below for the US which shows the percentage of people who say they are “very happy”, versus real GDP per person. As income has gone up over the last 50 years, happiness has fallen.

Source: US General Social Survey, IMF, AMP

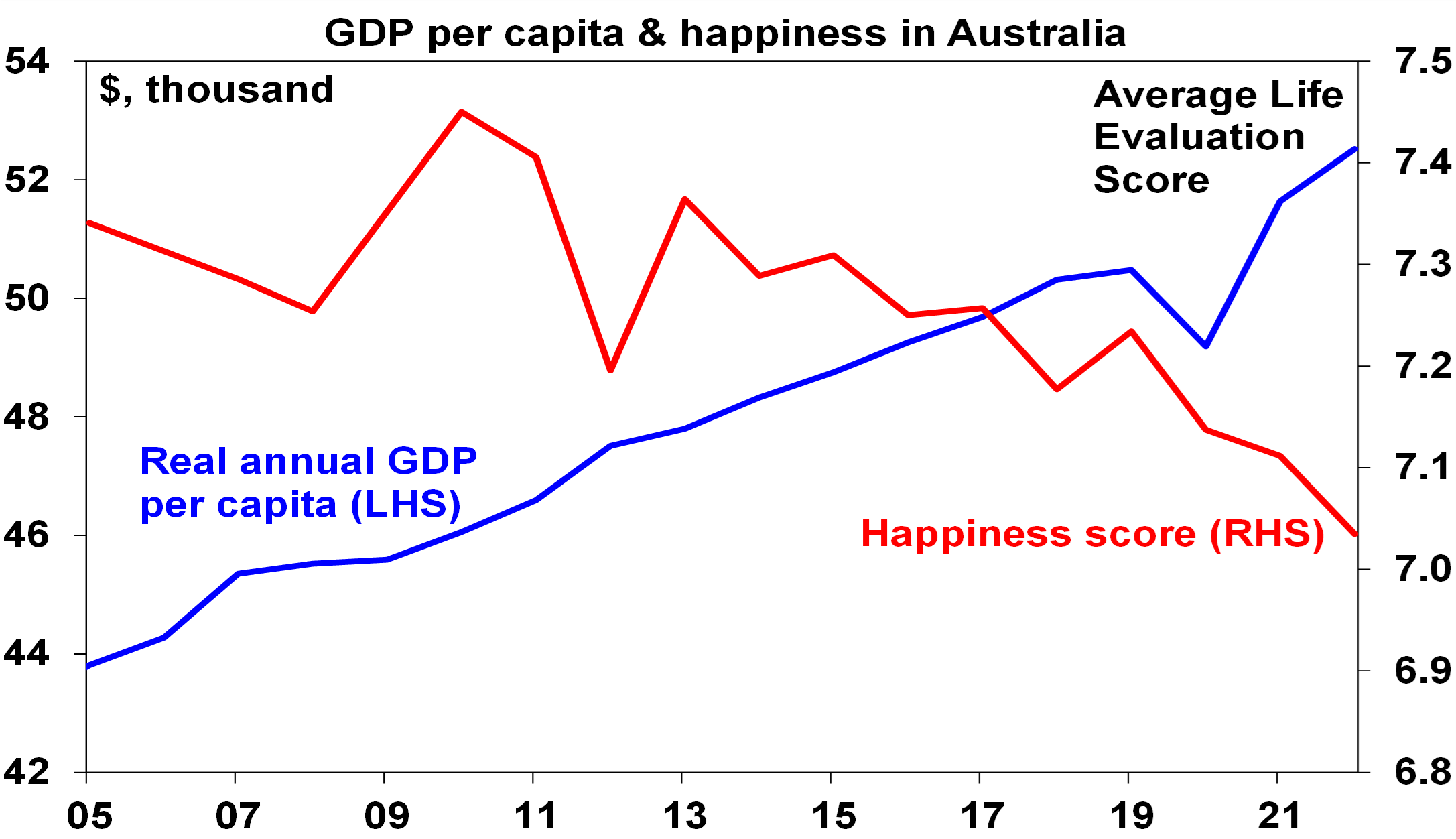

It’s a similar picture for Australia, although we only have Australian happiness data (from the World Happiness Report) for the last 20 years.

Source: World Happiness Report, ABS, AMP

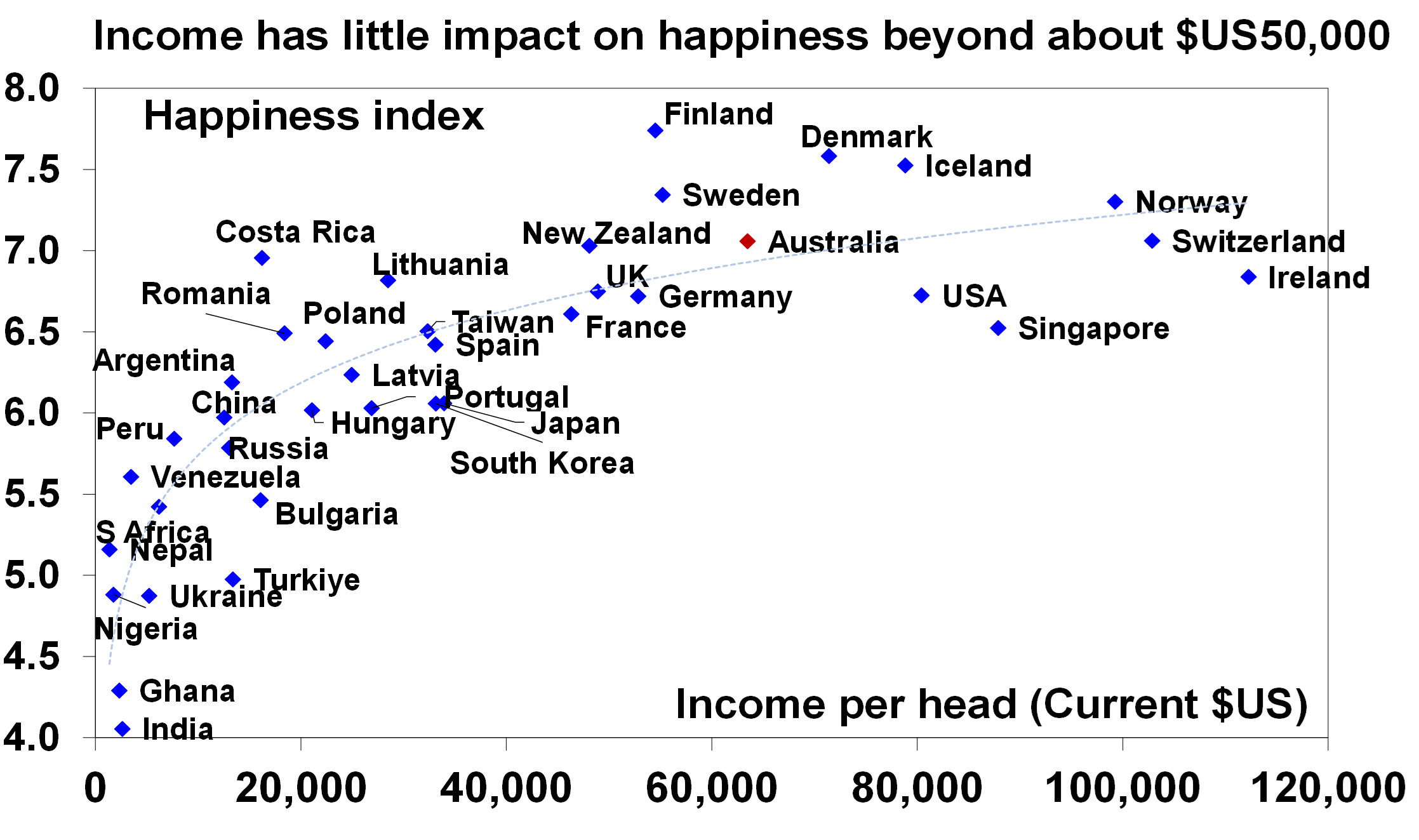

Stagnant or falling happiness is confirmed by rising trends in crime rates, depression diagnoses, suicide rates & drug abuse. This doesn’t mean there is no link between income and happiness. The next chart compares income levels and happiness across countries. At low levels of income, extra income can have a big positive impact on happiness. But for countries beyond a certain level (around $US50,000), extra income has little impact.

Source: World Happiness Report 2024, IMF, AMP

This is not to say that happiness is not high in rich countries. In fact, according to the World Happiness Report for 2024 Finland ranks #1 as the most happy and Australia ranks #10 with the US at #23. Lebanon and Afghanistan rank at the bottom at #142 and #143. It’s just that in rich countries variations in income across countries have little impact on happiness. Other findings from the happiness studies are as follows:

- Rich people are happier than poor people. This does not mean that society as a whole becomes happier as aggregate income for everyone rises. This has become known as the Easterlin paradox.

- People compare themselves to others (keeping up with the Joneses) in determining their happiness so if average incomes rise they may feel no happier, which may explain the Easterlin paradox.

- Women tend to report higher life satisfaction than men, but also experience more negative emotions, suggesting they are less happy.

- Married men are happier than unmarried men, but it’s less clear for women with some studies showing the opposite.

- Younger people in the US, Canada, Australia and NZ are the least happy age group. This is a major change from 20 years ago and may be due to the rise of social media giving rise to increased anxiety and depression amongst the young, particularly young girls. Poor housing affordability may also be impacting.

- Progressives are sadder than conservatives – possibly because they are more empathetic and focussed on a more negative world view.

- Physical & outdoor leisure, shopping, reading books, seeing relatives, listening to music and attending sporting and cultural events are associated with higher happiness. Time on the internet and TV is not.

- People in individualistic societies are happier and freedom to make life choices contributes to happiness.

- People adapt to their situation with evidence we are born with a genetically pre-set level of happiness to which we return to after good events (like winning the lottery) and bad (like having an accident).

Some have claimed that most people are on an “hedonic treadmill” of working ever harder to attain material wealth in the belief this will make them happier only to find it doesn’t but resolving to work even harder.

From GDP to Gross National Happiness?

Many argue these findings present a challenge for economists. Economics is about maximising “utility”, or happiness. But since happiness is hard to measure, economists assume a good proxy is income and consumption. If consumption is positively correlated with happiness, then policies to boost economic growth will boost happiness. But, if not, this may be misplaced. There are two schools of thought in relation to all of this. The first is to argue economic policy needs to be refocused on broader measures of wellbeing such as Gross National Happiness. The second argues that it is up to the individual to learn how to become happy. The first approach would mean a radical change in economic policy with proposals to boost happiness like these: tax excessive work (as it doesn’t lead to happiness); re-distribute income (because inequality leads to envy and keeps people on the “hedonic treadmill”); reduce the focus on competition and rivalry; spend more money on public goods such as parks; refocus on community; limit advertising to information to avoid creating demand for stuff we don’t need; and switch to focussing on Gross National Happiness.

This would have big implications for investors, as these policies would lead to slower profit growth and lower returns from growth assets.

Legislating for happiness makes little sense

However, there are good reasons to be sceptical of proposals for government policy to target happiness:

Firstly, happiness is very hard to measure, making some of the findings referred to above questionable, and impossible to define objectively. Nationally determined concepts of happiness, such as Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness concept, depend critically on subjective judgements that governments (or ethnic or religious majorities) may define to suit them. This can be used to justify religious or ethnic persecution and can be used to advance authoritarian aims.

Secondly, just because we get used to something doesn’t mean we should stop doing it. Rising material wealth may not permanently boost happiness beyond a certain level because we adapt to it. It would have been expected that the huge increase in healthy lifespans or the increase in measured leisure time would have boosted happiness, but it hasn’t. That does not mean we should cut back on health spending or reduce leisure. Policies to increase happiness by cutting work effort or income by redirecting people to other activities may flounder as those activities have the same problems as money, ie, people just get used to them.

Thirdly, while material progress may not be boosting happiness it is doubtful stagnation will either. Curiosity and the desire to advance are fundamental to humanity. Introducing policies to reduce work effort may reduce happiness by suppressing a sense of achievement. Oppression of individual advancement may explain low happiness in socialist countries.

Fourth, restricting choice in favour of officially mandated happiness guidelines may actually reduce happiness as evidence suggests that freedom to make life choices contributes to happiness.

Finally, we are partly dealing here with the outworking of success. The rise in affluence has given people in rich countries the time and money to search for happiness. It should also be recognised that the problems with social media and the decline in happiness it may be contributing to is also a problem of the economic success that gave rise to the technology, wealth and time that facilitate their use. Finding better ways to live with the success that has given rise to social media – a bit like the rules we set around driving cars – is arguably better than threatening to reverse it.

This is not to say that governments should not attempt to measure and boost wider measures of social welfare beyond GDP. But there is a danger in trying to legislate for happiness. There is nothing new in the concept that material wealth won’t lead to lasting happiness. Most religions have long been pointing it out. Buddha long ago observed that most human suffering comes from desire and this has to brought under control to achieve happiness. But seeking happiness and enlightenment is up to individuals, not the state. Maybe Thomas Jefferson was on to something when he wrote in the US Declaration of Independence that all people had the right to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” with the implication that happiness is something we can only pursue.

Bloomberg Launches Sustainability Screening Tool for Investors

ESG TOOLS, SERVICES/ INVESTORS Susan Lahey April 30, 2024

Business and financial markets information service provider Bloomberg announced the launch of a new tool aimed at helping investors assess and screen portfolios, funds and indices based customized sustainability criteria and thresholds, available on the Bloomberg Terminal.

According to Bloomberg, the new tool aims to help investors make investment decisions and meet regulatory compliance, amidst a diversification of sustainable investment strategies, and as regulators globally require investors to assess if the companies they invest in are meeting sustainability thresholds.

Patricia Torres, Global Head of Sustainable Finance Solutions at Bloomberg, said:

“Sustainability objectives vary from investor to investor, and from product to product. It can be difficult to fully understand whether a portfolio, fund or index meets your own definition of a sustainable investment.”

Using the new tool, investors are able to select from a wide range of criteria and input precise thresholds from categories including sustainability targets, exclusion or “no harm” criteria, and good governance requirements, with the solution calculating a percentage figure that reveals how much of the portfolio, fund or index is aligned with the criteria, and providing a detailed list view of all holdings to detect outliers.

The tool also enables investors to check whether funds align with regulatory obligations, including the EU’s MiFID II suitability rules and Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), the UAE’s new sustainable finance framework, the UK FCA’s forthcoming sustainability disclosure requirements, and future SEC guidance on ESG disclosures and fund labelling. According to Bloomberg, the tool could be used to help assess whether a fund meets classification under the SFDR framework , and the percentage of sustainable investment reported by the fund itself.

Torres added:

“This new Bloomberg tool provides clarity and empowers the user to customize sustainable investment criteria to determine if portfolios, funds, or indices meet their requirements with confidence. Based on Bloomberg’s extensive range of company ESG data, proprietary metrics and scores, the tool enables investors to assess investments in a comparable and scalable way.”

ESG Reporting

II hope you have enjoyed this week’s read. If you would like to discuss your investment journey, please feel free to reach out to me.

Regards,

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

a. Level 3, ADF Haus, Musgrave St., Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea

p. PO Box 2064, Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814