6 May, 2024

Hello and welcome to this week’s JMP Report,

Hello and welcome to this week’s JMP Market Report,

On the equity front we saw 3 stocks trade on the local market. BSP traded 938 shares, closing 4t higher to close at 16.81. KSL traded 268,327 shares, closing 1t lower at K2.91 and NGP traded 45,000 shares closing 1t higher at K0.70.

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT | 6 May, 2024 – 11 May, 2024

| STOCK | QUANTITY | CLOSING PRICE | BID | OFFER | CHANGE | % CHANGE | 2023 INTERIM | 2023 FINAL DIV | YIELD % | EX-DATE | RECORD DATE | PAYMENT DATE | DRP |

| BSP | 938 | 16.80 | 16.81 | – | 0.04 | 0.24 | K0.370 | K1.060 | 8.87 | TUE 27 FEB 2024 | WED 28 FEB 2024 | FRI 22 MAR 2024 | NO |

| KSL | 268,327 | 2.9 | 2.81 | 2.91 | -0.01 | -0.34 | K0.097 | K0.159 | 8.82 | TUE 4 MAR 2024 | WED 6 MAR 2024 | MON 15 APR 2024 | YES |

| STO | – | 19.37 | 19.37 | – | – | 0.00 | K0.314 | K0.660 | 5.04 | MON 26 FEB 2024 | TUE 27 FEB 2024 | TUE 26 MAR 2024 | – |

| NEM | – | 145.00 | 145.00 | 145.00 | – | 0.00 | – | USD 0.250 | 0.63 | MON 4 MAR 2024 | TUE 5 MAR 2024 | WED 27 MAR 2024 | – |

| KAM | – | 1.20 | 1.16 | – | 0.05 | 4.17 | K0.12 | – | – | – | – | – | YES |

| NGP | 45000 | 0.70 | – | – | 0.01 | 1.43 | K0.03 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CCP | – | 2.16 | 2.15 | – | – | 0.93 | K0.110 | K0.131 | 6.21 | FRI 22 MAR 2024 | WED 27 MAR 2024 | FRI 19 APR 2024 | NO |

| CPL | – | 0.79 | – | 0.79 | – | 0.00 | – |

– | – |

– | – | – | – |

| SST | – | 45.00 | – | 50.00 | – | 0.00 | K0.35 | K0.60* | 1.33 | WED 24 APR 2024 | FRI 26 APR 2024 | FRI 26 JULY 2024 | NO |

Dual listed PNGX/ASX

BFL – 6.30 +33c

KSL – 93.5c -.5c

NEM – 64.37 + 2.35

STO – 7.86 +38c

Interest Rates

On the Interest Rate front we saw the Bank take 2.09bn of liquidity from the system and raised the rate from 2% to at 2.50% through their issuance of the 7 day Central Bank Bills.

In the TBill market we saw 364 TBills weaken a little further to 3.77% up from 3.70% with the market oversubscribed by 56mill. Rates for 12 month finance company money remain steady with Fincorp and Credit Corp offering 2.35%.

Bank PNG announced the next GIS auction which will be held Tuesday, May 14th. A total of 600million GIS is on offer, ranging from 2yr through to 10 year maturities.

Other assets we like to monitor

Gold – 2360 +$58

Palladium – 979 +$29

Platinum – 999 +$41

Silver – 28 +$1.44

Bitcoin – 61,237 -4%

Ethereum – 2927 -6.6%

What we have been reading

WARNING – Economy ‘Murderer’ at Large

Posted 09/05/2024 – Ainslie Gold

Gold is the truly uncorrelated asset that is the world’s go-to when financial and/or geopolitical crises hit. The problem with such crises is you generally don’t get a warning. Call it a ‘Black Swan’ or whatever term you like, fixating on a single or few metrics to tell you when it will happen will more often leave you surprised and unprepared. ‘Better a year too early than a day too late’ is the oft repeated mantra of those who understand. Bianco Research’s Jim Bianco topically just tweeted the following, and it’s a salient reminder.

“There has been much talk about a pending recession … again!

Keep this in mind.

Economist Rudi Dornbusch is known to have said that economic expansions do not die of old age; they are murdered.

This has been true for the last 50 years:

2020 = COVID

2008 = Financial Crisis, $145 crude oil [we’d argue oil came later, it was simply the ‘bad debt’ of subprime exploding]

2001 = Tech crash/9/11

1991 = Iraq invaded Kuwait (400% rise in crude)

1982 = 200-year high in interest rates

1980 100-year high in inflation

1974 = Arab Oil Embargo

Too many think the economy will either roll over or “pop.” It does not work that way. It does not die of old age.

In a capitalist economy, investors, like most of those reading this, give money to good ideas and take it away from bad ideas. This means the economy continuously self-adjusts, so the natural state is to expand and grow 90% of the time.

The other 10% of the time is a recession because something murders it.

So, all the talk about deficits and inflation will not cause a recession. However, these issues can, and probably do, make the economy vulnerable to “murder.” But it will still take that murder to cause a recession. Think pandemic, spiking crude oil, political crisis, all of the above simultaneously.

This unexpected event(s) could be later this year, in 10 years, or anywhere between. It really cannot be predicted, like COVID, especially by economists.

This is not a knock on economists. No amount of analysis of payroll numbers or inflation reports can tell you a pandemic, a spike in oil prices, or a political crisis is coming.

How do we know when the murder has happened? Investors lose a lot of money. A recession means that even investors’ good ideas act like bad ones.”

Our current world economic order is a flock of ‘black swans’ waiting to emerge from the clouds. Simply, the world’s debt splurge since we left the gold standard is quickly reaching a secular ‘Minsky Moment’ where the debt burden is simply too great and no amount of printing new money to pay the interest on the debt created to print the last lot of money will work, and meaningful growth can’t occur under its weight. The murder weapon could quite simply be interest rates. Gold stands apart from ALL other assets as the asset proven to go up in value with the pre-emptive liquidity injections keeping the Ponzi Scheme alive and also the asset that goes up, or at the very least stays steady as the system collapses. History is littered with the latter occurring time and time again with regularity as human greed and ‘this time is different’ hubris repeats.

We have shared the chart below courtesy of Crescat Capital putting all of that into further context. Yes, the gold price has been great this year, but it’s likely only just beginning whilst the murderer is at large.

Thank you Ainslie Golf for this article

We might be closer to changing course on climate change than we realised: Greenhouse gas emissions might have already peaked. Now they need to fall — fast.

By Umair Irfan

The world might soon see a sustained decline in greenhouse gas emissions.

Umair Irfan is a correspondent at Vox writing about climate change, Covid-19, and energy policy. Irfan is also a regular contributor to the radio program Science Friday. Prior to Vox, he was a reporter for ClimateWire at E&E News.

Earth is coming out of the hottest year on record, amplifying the destruction from hurricanes, wildfires, heat waves, and drought. The oceans remain alarmingly warm, triggering the fourth global coral bleaching event in history. Concentrations of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere have reached levels not seen on this planet for millions of years, while humanity’s demand for the fossil fuels that produce this pollution is the highest it has ever been.

Yet at the same time, the world may be closer than ever to turning a corner in the effort to corral climate change.

Last year, more solar panels were installed in China — the world’s largest carbon emitter — than the US has installed in its entire history. More electric vehicles were sold worldwide than ever. Energy efficiency is improving. Dozens of countries are widening the gap between their economic growth and their greenhouse gas emissions. And governments stepped up their ambitions to curb their impact on the climate, particularly when it comes to potent greenhouse gases like methane. If these trends continue, global emissions may actually start to decline.

Climate Analytics, a think tank, published a report last November that raised the intriguing possibility that the worst of our impact on the climate might be behind us.

“We find there is a 70% chance that emissions start falling in 2024 if current clean technology growth trends continue and some progress is made to cut non-CO2 emissions,” authors wrote. “This would make 2023 the year of peak emissions.”

“It was actually a result that surprised us as well,” said Neil Grant, a climate and energy analyst at Climate Analytics and a co-author of the report. “It’s rare in the climate space that you get good news like this.”

The inertia behind this trend toward lower emissions is so immense that even politics can only slow it down, not stop it. Many of the worst-case climate scenarios imagined in past decades are now much less likely.

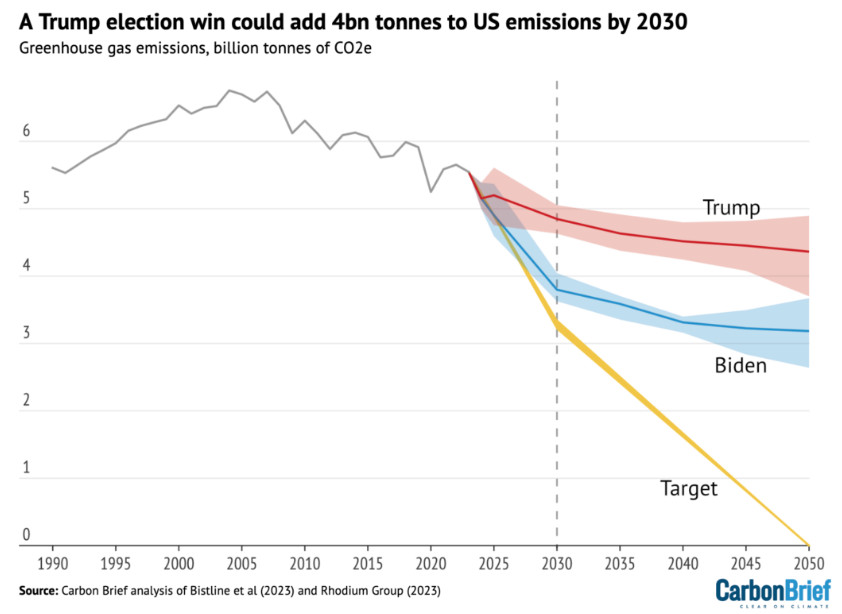

The United States, the world’s second largest greenhouse gas emitter, has already climbed down from its peak in 2005 and is descending further. In March, Carbon Brief conducted an analysis of how US greenhouse gas emissions would fare under a second Trump or a second Biden administration.

They found that Trump’s stated goals of boosting fossil fuel development and scrapping climate policies would increase US emissions by 4 billion metric tons by 2030. But even under Trump, US emissions are likely to slide downward.

This is a clear sign that efforts to limit climate change are having a durable impact.

US emissions are on track to decline regardless of who wins the White House in November, but current policies are not yet in line with US climate goals. Carbon Brief

However, four months into 2024, it seems unlikely that the world has reached the top of the mountain just yet. Fossil fuel demand is still poised to rise further in part because of more economic growth in developing countries. Technologies like artificial intelligence and cryptocurrencies are raising overall energy demand as well.

Still, that it’s possible at all to conceive of bending the curve in the near term after more than a century of relentless growth shows that there’s a radical change underway in the relationship between energy, prosperity, and pollution — that standards of living can go up even as emissions from coal, oil, and gas go down.

Greenhouse gases are not a runaway rocket, but a massive, slow-turning cargo ship. It took decades of technology development, years of global bickering, and billions of dollars to wrench its rudder in the right direction, and it’s unlikely to change course fast enough to meet the most ambitious climate change targets.

But once underway, it will be hard to stop.

We might be close to an inflection point on greenhouse gas emissions

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, greenhouse gas emissions have risen in tandem with wealth and an expanding population. Since the 1990s and the 2000s, that direct link has been separated in at least 30 countries, including the US, Singapore, Japan, and the United Kingdom. Their economies have grown while their impact on the climate has shrunk per person.

In the past decade, the rate of global carbon dioxide pollution has held fairly level or risen slowly even as the global economy and population has grown by wider margins. Worldwide per capita emissions have also held steady over the past decade.

“We can be fairly confident that we’ve flattened the curve,” said Michael Lazarus, a senior scientist at SEI US, an environmental think tank, who was not involved in the Climate Analytics study.

Still, this means that humanity is adding to the total amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — and doing so at close to its fastest pace ever.

It’s good that this pace is at least not accelerating, but the plateau implies a world that will continue to get warmer. To halt rising temperatures, humans will have to stop emitting greenhouse gases, zeroing their net output, and even start withdrawing the carbon previously emitted. The world thus needs another drastic downward turn in its emissions trajectory to limit climate change. “I wouldn’t get out any balloons or fireworks over flattening emissions,” Lazarus said.

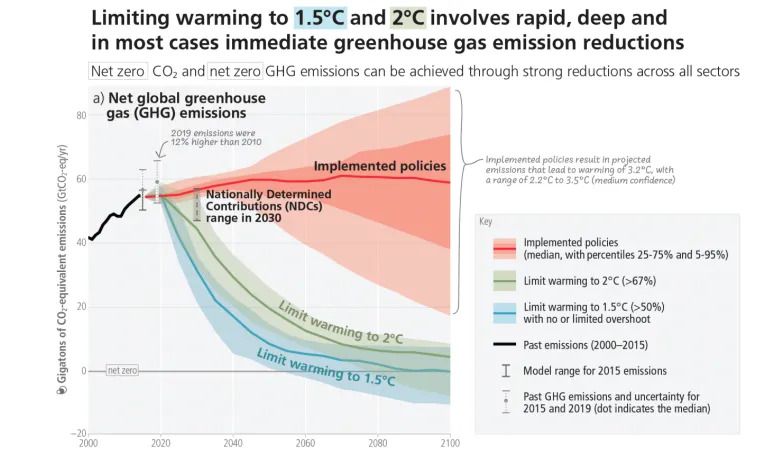

Then there’s the clock. In order to meet the Paris climate agreement target of limiting warming this century to less than 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) on average above pre-industrial temperatures, the world must slash carbon dioxide emissions in half by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050. That means power generators, trucks, aircraft, farms, construction sites, home appliances, and manufacturing plants all over the world will have to rapidly clean up.

The current round of international climate commitments puts the planet on track to warm by 5.4°F (3°C) by the end of the century. That’s a world in which the likelihood of a major heat wave in a given year would more than double compared to 2.7°F of warming, where extreme rainfall events would almost double, and more than one in 10 people would face threats from sea level rise.

“That puts us in this race between the really limited time left to bend the emissions curve and start that project towards zero, but we are also seeing this sort of huge growth, an acceleration in clean technology deployment,” Grant said. “And so we wanted to see which of these factors is winning the race at the moment and where we are at.”

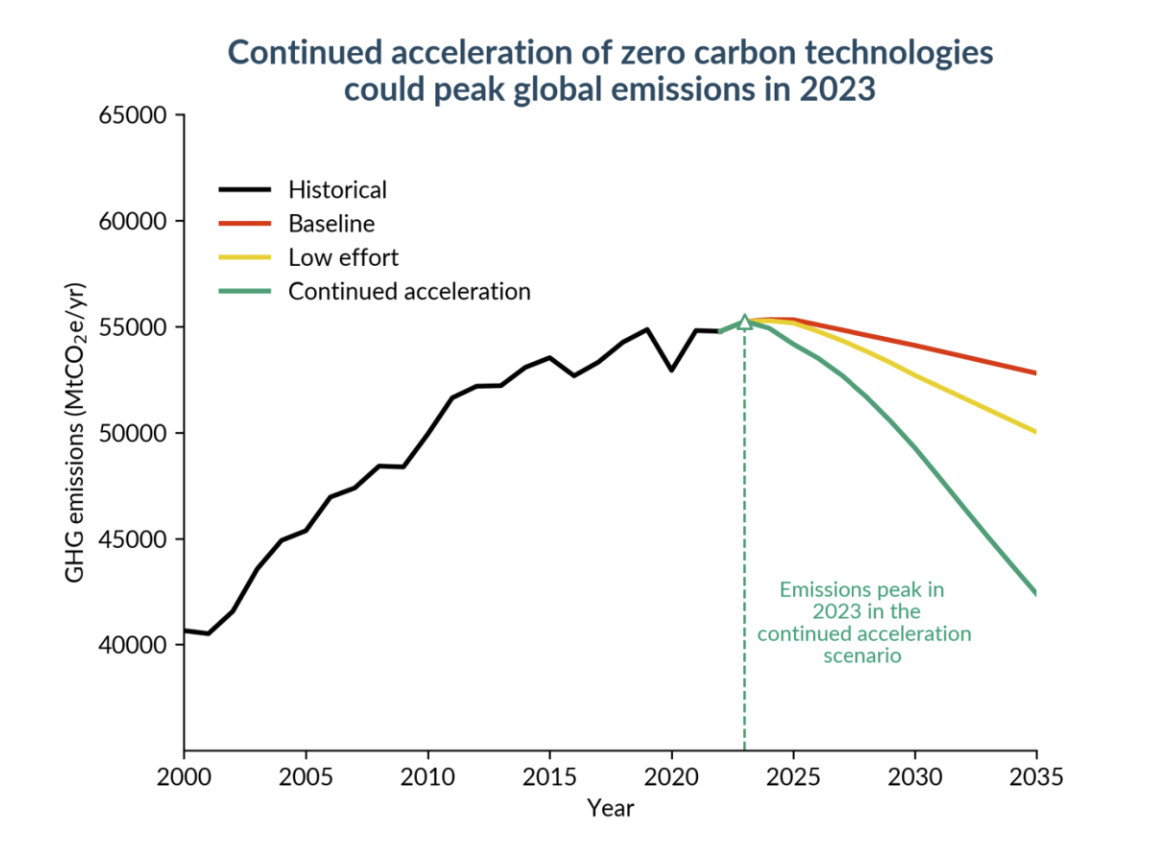

Grant and his team mapped out three scenarios. The first is a baseline based on forecasts from the International Energy Agency on how current climate policies and commitments would play out. It shows that fossil fuel-related carbon dioxide emissions would reach a peak this year, but emissions of other heat-trapping gases like methane and hydrofluorocarbons would keep rising, so overall greenhouse gas emissions would level off.

The second scenario, dubbed “low effort,” builds on the first, but also assumes that countries will begin to fulfill their promises under agreements like the Global Methane Pledge to cut methane pollution 30 percent from 2020 levels by 2030 and the Kigali Amendment to phase out HFCs. Under this pathway, total global emissions reach their apex in 2025.

The third scenario imagines a world where clean technology — renewable energy, electric vehicles, energy efficiency — continues gaining ground at current rates, outstripping energy demand growth and displacing coal, oil, and natural gas. That would mean greenhouse gases would have already peaked in 2023 and are now on a long, sustained decline.

Global greenhouse gas emissions are likely to fall in the coming years, but the rate of decline depends on policies and technology development. Climate Analytics

Global greenhouse gas emissions are likely to fall in the coming years, but the rate of decline depends on policies and technology development. Climate Analytics

The stories look different when you zoom in to individual countries, however. While overall emissions are poised to decline, some developing countries will continue to see their output grow while wealthier countries make bigger cuts.

As noted, the US has already climbed down from its peak. China expects to see its emissions curve change directions by 2025. India, the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emitter, may see its emissions grow until 2045.

All three of these pathways anticipate some sort of peak in global emissions before the end of the decade, illustrating that the world has many of the tools it needs to address climate change and that a lot of work in deploying clean energy and cleaning up the biggest polluters is already in progress.

There will still be year-to-year variations from phenomena like El Niño that can raise electricity demand during heat waves or shocks like pandemics that reduce travel or conflicts that force countries to change their energy priorities. But according to the report, the overall trend over decades is still downward.

To be clear, the Carbon Analytics study is one of the more optimistic projections out there, but it’s not that far off from what other groups have found. In its own analysis, the International Energy Agency reports that global carbon dioxide emissions “are set to peak this decade.” The consulting firm McKinsey anticipates that greenhouse gases will begin to decline before 2030, also finding that 2023 may have been the apogee.

GLOBAL EMISSIONS COULD JUST AS EASILY SHOOT BACK UP IF GOVERNMENTS AND COMPANIES GIVE UP ON THEIR GOALS

Within the energy sector, Ember, a think tank, found that emissions might have peaked in 2022. Research firm Rystad Energy expects that fossil fuel emissions will reach their pinnacle in 2025.

Bending the curve still requires even more deliberate, thoughtful efforts to address climate change — policies to limit emissions, deploying clean energy, doing more with less, and innovation. Conversely, global emissions could just as easily shoot back up if governments and companies give up on their goals.

“Peaking is absolutely not a guarantee,” Grant said. And if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, even at a slower rate, Earth will continue heating up. It means more polar ice will melt, lifting sea levels along every ocean, increasing storm surges and floods during cyclones. It means more dangerous heat waves. It means more parts of the world will be unlivable.

We’re close to bending the curve — but that doesn’t mean the rest will be easy

There are some other caveats to consider. One is that it’s tricky to simply get a full tally of humanity’s total impact on the climate. Scientists can measure carbon dioxide concentrations in the sky, but it’s tougher to trace where those molecules came from.

Burning fossil fuels is the dominant way humans add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Since they’re closely tracked commercial commodities, there are robust estimates for their contributions to climate change and how they change over time.

But humans are also degrading natural carbon-absorbing ecosystems like mangrove forests. Losing carbon sinks increases the net amount of carbon dioxide in the air. Altering how we use land, like clearing forests for farms, also shifts the balance of carbon. These changes can have further knock-on effects for the environment, and ecosystems like tropical rainforests could reach tipping points where they undergo irreversible, self-propagating shifts that limit how much carbon they can absorb.

All this makes it hard to nail down a specific time frame for when emissions will peak and what the consequences will be.

There’s also the thorny business of figuring out who is accountable for which emissions. Fossil fuels are traded across borders, and it’s not always clear whose ledger high-polluting sectors like international aviation and shipping should fall on. Depending on the methodology, these gray areas can lead to double-counting or under-counting.

“It’s very difficult to get a complete picture, and even if we get the little bits and pieces, there’s a lot of uncertainty,” said Luca Lo Re, climate and energy analyst at the IEA.

Even with these uncertainties, it’s clear that the scale of the course correction needed to meet climate goals is immense.

According to the Climate Analytics report, to meet the 2030 targets for cutting emissions, the world will need to stop deforestation, stop any new fossil fuel development, double energy efficiency, and triple renewable energy.

Another way to illustrate the enormity of this task is the Covid-19 pandemic. The world experienced a sudden drop in global emissions as travel shut down, businesses closed, people stayed home, and economies shrank. Carbon dioxide output has now rebounded to an even higher level.

Reducing emissions on an even larger scale without increasing suffering — in fact, improving welfare for more people — will require not just clean technology but careful policy. Seeing emissions level off or decline in many parts of the world as economies have grown in recent decades outside of the pandemic is an important validation that the efforts to limit climate change are having their intended effect. “Emissions need to decrease for the right reasons,” Lo Re said. “It is reasonable to believe our efforts are working.”

The mounting challenge is that energy demand is poised to grow. Even though many countries have decoupled their emissions from their GDPs, those emissions are still growing. Many governments are also contending with higher interest rates, making it harder to finance new clean energy development just as the world needs a massive buildout of solar panels, wind turbines, and transmission lines.

And peaking emissions isn’t enough: They have to fall. Fast.

The longer it takes to reach the apex, the steeper the drop-off needed on the other side in order to meet climate goals. Right now, the world is poised to walk down a gentle sloping hill of greenhouse gas emissions instead of the plummeting roller coaster required to limit warming this century to less than 2.7°F/1.5°C. It’s increasingly unlikely that this goal is achievable.

To meet global climate targets, greenhouse gas emissions need to fall precipitously. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

To meet global climate targets, greenhouse gas emissions need to fall precipitously. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Finally, the ultimate validation of peak greenhouse emissions and a sustained decline can only be determined with hindsight. “We can’t know if we peaked in 2023 until we get to 2030,” said Lazarus.

The world may be closer than ever to bending the curve on greenhouse gas emissions downward, but those final few degrees of inflection may be the hardest.

The next few years will shape the warming trajectory for much of the rest of the century, but obstacles ranging from political turmoil to international conflict to higher interest rates could slow progress against climate change just as decarbonization needs to accelerate.

“We should be humble,” Grant said. “The future is yet unwritten and is in our hands.”

EPA Boosts Emissions Reporting Requirements for Oil & Gas Companies

Mark Segal May 7, 2024

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced that it has issued a finalized rule aimed at strengthening and expanding methane emissions reporting requirements for oil and natural gas facility owners and operators, and improving the quality of emissions data reported through the use of advanced technologies.

Rapid reduction in methane emissions is seen as one of the most effective near-term actions that can be taken in order to help achieve the global climate goal to limit warming to 1.5°C. Methane is an extremely potent greenhouse gas (GHG), with as much as 80x the warming power of CO2, and oil and gas facilities are the largest industrial source of methane emissions in the U.S.

Addressing methane emissions has formed a key part of the Biden administration’s climate strategy, with actions taken including the launch in 2022 by the administration of its Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan, including a commitment of more than $20 billion in new investments to tackle methane emissions. allocated from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the Inflation Reduction Act, in addition to annual appropriations.

The new final rule updates the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP) requirements for the petroleum and natural gas sector, which mandates reporting of GHG data and other relevant information from large GHG emission sources, fuel and industrial gas suppliers, and CO2 injection sites in the U.S.

According to the EPA, the new rule comes to address reporting gaps in the GHGRP, with studies indicating that actual emissions from oil and gas facilities are much greater than has been historically reported under the GHGRP. The new rule aims to address the gap with changes including the facilitation of satellite data to identify super-emitters and quantify large emission events and requirements for direct monitoring of key emission sources, as well as updated methods for calculation.

The EPA added that going forward, it will solicit input on the use of advanced measurement data and methods included in the revised rule to consider future rulemaking for the use of these technologies beyond that already included in the rule, and pledged to conduct engagements to learn about technological advances for measurement and detection technologies, and their appropriateness for use in regulatory reporting programs.

EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan said:

“As we implement the historic climate programs under President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, EPA is applying the latest tools, cutting edge technology, and expertise to track and measure methane emissions from the oil and gas industry. Together, a combination of strong standards, good monitoring and reporting, and historic investments to cut methane pollution will ensure the U.S. leads in the global transition to a clean energy economy.”

I hope you have enjoyed our report this week, if you would like to have a chat regarding your investment journey, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Regards,

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

a. Level 3, ADF Haus, Musgrave St., Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea

p. PO Box 2064, Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814