6 June, 2022

Welcome to this week’s JMP Weekly Report

On the equity front

Trading in the local bourse was quiet last week. The two stocks that traded were BSP and KSL. BSP saw 29,708 shares change hands closing unchanged at K12.30 while KSL saw 61,239 shares trade closing unchanged at K3.00 on Friday. All other stocks had NIL trades in their securities. Details below;

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT | 30 May, 2022 – 3 June, 2022

| STOCK | QUANTITY | CLOSING PRICE | CHANGE | % CHANGE | 2021 FINAL DIV | 2021 INTERIM | YIELD % | EX-DATE | RECORD DATE | PAYMENT DATE | DRP |

| BSP | 29,708 | 12.30 | – | – | K1.3400 | – | 11.61 | THU 10 MAR | FRI 11 MAR | FRI 22 APR | NO |

| KSL | 61,239 | 3.00 | – | – | K0.1850 | – | 7.74 | THU 3 MAR | FRI 4 MAR | FRI 8 APR | NO |

| STO | – | 19.00 | – | – | K0.2993 | – | – | MON 21 FEB | TUE 22 FEB | THU 24 MAR | – |

| KAM | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | – | 10.00 | – | – | – | YES |

| NCM | – | 75.00 | – | – | USD$0.075 | – | – | FRI 25 FEB | MON 28 FEB | THU 31 MAR | – |

| NGP | – | 0.70 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CCP | – | 1.85 | – | – | – | – | 6.19 | – | – | – | YES |

| CPL | – | 0.95 | – | – | – | – |

– | – | – | – | – |

Dual listed ASX/POMX stocks

BFL – $4.97 steady

KSL – $0.87 down – 1c

NCM – 24.64 -37c

STO – $8.40 +20c

This week’s order book

We have orders on both sides of most stocks and I am a nett buyer of BSP

You may also like

Gold Standard $US59.11 ( Down $0.53 / 0.88%) $AU82.29 ( Down $0.63 / 0.75%)

Silver Standard $US0.69 ( Down $0.01 / 1.42%) $AU0.96 ( Down $0.01 / 1.03%)

Bitcoin $US31,810 ( Up $113 / 0.35%) $AU44,285 ( Up $213 / 0.48%)

Ethereum $US1945 ( Down $46 / 2.31%) $AU2707 ( Down $61 / 2.20%)

Litecoin $US68.42 ( Down $0.58 / 0.84%) $AU95.25 ( Down $0.68 / 0.70%)

Ripple $US0.42 ( Up $0.01 / 2.43%) $AU0.584 ( Up $0.014 / 2.45%)

Bitcoin Cash $US205 ( Up $8 / 4.06%) $AU285 ( Up $12 / 4.39%)

Theta $US1.35 ( Up $0.03 / 2.27%) $AU1.879 ( Up $0.044 / 2.39%)

Tron $US0.08 ( Up $0 / 0.00%) $AU0.111 ( Up $0 / 0.00%)

Cardano $US0.63 ( Up $0.07 / 12.50%) $AU0.877 ( Up $0.099 / 12.72%)

Stellar $US0.15 ( Up $0.01 / 7.14%) $AU0.208 ( Up $0.014 / 7.21%)

Chainlink $US7 ( Up $0 / 0.00%) $AU9 ( Up $0 / 0.00%)

Matic $US0.66 ( Up $0.01 / 1.53%) $AU0.91 ( Up $0.01 / 1.11%)

Interest rate market

On the interest rate front, we saw the short end bid hard again with the 364 day auction averaging 2.98%, that is a drop of 52bpts in two weeks. So how far does this go? In the 12 mth Finance company depo market, both CCP and Fincorp are still paying 4.60% for deposits. So a 1.63% spread between Government TBills and Commercial rates for 12mth money?

There was an announcement of a GIS Tender, details provided but no results at hand.

What we’ve been reading this week

Beware: 100% green energy could destroy the planet

by Stephen Moore

Getty Images

The untold story about “green energy” is that it can’t possibly be scaled up to provide anywhere near the energy to replace fossil fuels. (Unless we are headed back to the stone ages, which is what some of the “de-growth” advocates favour).

Right now, the United States gets 70% of its energy from fossil fuels. To go to zero over the next 20 years would be economically catastrophic and cost tens of millions of jobs. With gas prices at nearly double their price back from when Trump left office and inflation up from 1.5% to 8% in just 15 months, we are already experiencing the economic damage from the green energy crusaders.

But we also have to ask whether green energy is even good for the environment. Some environmentalists are pointing to a little-noticed study by the World Bank showing that moving toward 100% solar, wind, and electric battery energy would be “just as destructive to the planet as fossil fuels.” This was precisely the conclusion of a story in Foreign Policy magazine, hardly a right-wing publication.

According to the Foreign Policy analysis, moving to a “carbon-free” energy future “requires massive amounts of energy, not to mention the extraction of minerals and metals at great environmental and social costs.”

Here are some of the numbers. Going all-in on batteries, solar, and wind would require

- Thirty-four million metric tons of copper,

- Forty million tons of lead,

- Fifty million tons of zinc,

- One hundred and sixty-two million tons of aluminium,

- Four-point-eight billion tons of iron.

Those tens of millions of windmills, solar panels, and electric batteries for cars and trucks aren’t exactly biodegradable. So, we will have the most prominent energy graveyard with toxic pollutants that will be 100 times larger than any nuclear waste storage. And yet, the Left is worried about plastic straws!

I’m all for mining for America’s bountiful natural resources of copper, lead, magnesium, and precious metals. But, ironically, it’s the greens that want to shut down mines, which is like saying you want food, but you oppose farming. Talk about cognitive dissonance.

Then, the land space is needed for the windmills and solar panels. Bloomberg reports that getting to zero carbon by 2050 would require a land area equal to five South Dakotas “to develop enough clean power to run all the electric vehicles, factories, and more.”

In other words, the liberals are calling for a full-scale industrialization of America’s wilderness and landscape.

Now, even many of the most liberal areas of the country are shouting “no” to green energy in their own backyard. Vermonters are rebelling against unsightly solar panels spoiling their views. According to the Bennington Banner, “Vermont’s utility regulator has rejected permits for two 2 MW solar farms proposed in Bennington, pointing to aesthetic concerns and current land conservation measures in the town plan.”

Meanwhile, a town in Wisconsin is suing state regulators to “stop construction” of what would be “the state’s largest solar project,” according to the Wisconsin Journal.

Even blue Massachusetts residents are fighting green energy projects. Off-shore wind farms are delayed off the coast of Cape Cod, where per capita income is nearly the highest in the country, because they don’t want their ocean views spoiled from their beach-front villas.

In other words, real nature lovers are finally starting to awaken to the reality that wind and solar aren’t so green after all. A nuclear plant takes up at most one square mile of land. Wind and solar farms require hundreds of thousands of acres. So, to provide enough electric power to keep Manhattan lit up at night would require paving over nearly the whole state of Connecticut with windmills and solar farms.

The public is starting to ask: How is any of this green? The Green New Deal strategy makes especially no sense given that by increasing our use of clean-burning and reliable natural gas, we are reducing energy prices AND cutting carbon emissions. Add nuclear power to the mix, and we wouldn’t need to start building wind and solar farms in our forests, deserts, and national parks.

Long-term investing in emerging markets

Rising middle classes will shape global trends.

Unfortunately, getting old can come with a stigma. Many people try to delay the inevitable with regular exercise, a healthy diet and a strict skincare regime. But time stops for no one.

Ageing can also be a problem for countries. Many developed markets are starting to struggle with ageing populations and their associated social and economic issues. By 2025, the number of “working age” people (15 to 64-year-olds) in high-income countries is expected to start declining, with Europe facing the most pronounced falls.

The emerging world will mostly still benefit from young populations, with rising numbers of working-age people. But several have exhausted their “demographic dividends” and can expect rising dependency ratios, which means fewer workers will need to support more retirees.

In society, we need to guard against ageism. That’s also true when thinking about economic growth.

Demographics are important

As well as affecting the total size of an economy through the number of people and workers, a shifting demographic profile has the potential to influence economies in other ways – via investment levels, interest rates and inflation, for example.

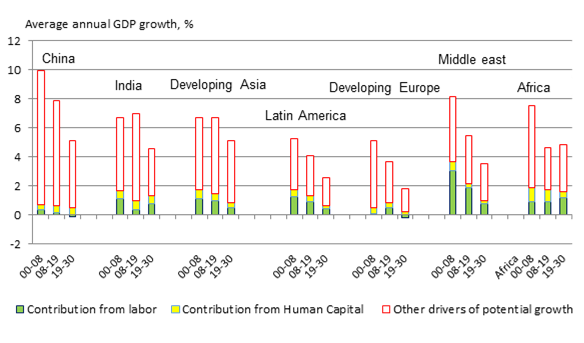

Across major emerging markets, the boost from rising labour forces may be starting to slow, but Developing Asia (excluding China and Thailand), the Middle East and Africa are still set to enjoy meaningful gains from their labour force (see chart, below).

This helps provide some level of confidence that emerging markets will maintain stronger growth potential in the near term and further out. The abrdn Research Institute expects that emerging markets are likely to grow twice as fast as Developed Markets in 2023 and 2024.

Source: abrdn

Demographics are not destiny

However, there are important caveats when considering how demographics may shape growth.

The application of simplistic and outdated definitions of “working-age” populations – often taken as 15 to 64-year-olds – fails to accurately capture rising labour force participation from 60 to 70-year-olds (because of rising life expectancy and later retirement).

An “older” workforce affects the calculation of dependency ratios. On a per-worker basis, dependency ratios will continue to fall over the next three decades in India – meaning that more workers support fewer retirees.

Meanwhile, ratios in emerging Asia and Latin America are little changed, rather than appearing to move adversely.

The quality of the workforce is just as important as the quantity

Human capital – the economic value of a worker’s skills and experience – has room to grow as more people stay in formal education for longer. This is likely to offset the drag from having fewer workers (or from a slowing pace of workforce growth).

Lower-income countries will benefit more. For example, many countries in Africa, and to a lesser extent India, should benefit from more workers and a more capable workforce. China could still offset fewer workers with better-educated ones (see yellow bars versus green bars in the chart above).

Importance of machinery and equipment

What’s more, quality-adjusted labour input – that is, workers plus human capital – rarely accounts for more than one-third of potential economic growth.

The building blocks of long-term economic growth also include productivity and capital investment (that is, the buildings, equipment and software available to workers, and how efficiently workers can combine them with their time).

Emerging markets still have considerable infrastructure needs, which help to lay a solid foundation for future growth. Less-developed countries typically have relatively low urbanisation rates. As these countries build more cities, this will drive considerable construction activity.

Moreover, abrdn expects economic growth in emerging markets to require a large increase in all types of capital investment – buildings, plant and machinery, vehicles, software and other forms of information technology – on a per-worker basis.

Directing capital to productive uses is difficult, but emerging markets have lower debt levels than Developed Markets, which suggest some wiggle room to help smooth their path.

Growth of the middle class

Even with some slowing of trend growth, emerging markets will account for more global consumption and the growth of the global middle class, in abrdn’s view.

In absolute terms, abrdn believes that China and India will increasingly dominate both the global and emerging markets landscape in 2050, given the size of their economies.

China’s economy could more than triple by 2050, while India’s could rise by a factor of 4, according to abrdn’s research. But even by 2050, Chinese per capita income is likely to remain well below that of the US. This implies that with the right structural reforms, China’s growth engine may not have run out of steam.

Compositional changes within China, India and elsewhere are even more striking than the overall growth figures.

Should the Chinese and Indian economies expand as abrdn projects, the size of their financial and consumer markets will also rise notably.

As a simple thought experiment, holding the ratio of market capitalisation to gross domestic product (GDP) fixed, equity market capitalisation could expand in China from US$8.5 trillion now to almost US$30 trillion by 2050, and in India from US$2.2 trillion to more than US$9 trillion (on abrdn calculations).

The rise of middle classes in emerging markets will also become a dominant force in shaping global trends. Chinese consumers are expected to be increasingly important as China gradually pivots away from its investment-intensive growth model.

Indeed, by 2040, China’s consumer market may have overtaken the US, and by 2050 it could be 20% bigger, abrdn research finds. Both China and India could see a quadrupling of consumption from current levels.

A global focus on sustainability

Finally, while China’s long-term growth story is attractive to investors, there are still questions about how compatible this is with an increasing focus on environmental, social and governance concerns.

China is moving away from an industry-heavy economy to a more balanced one, with a greater emphasis on services, and on restoring and protecting the environment. But challenges remain and the road will not always be smooth.

abrdn believes that a strong focus on due diligence and active engagement at the firm-level can help drive positive change, helping to progress the sustainability agenda.

abrdn is a leading global asset manager. abrdn funds are available through ASX via mFund.

Investing in a world with less money

Sam Morris

Fidante Partners ActiveX

Portfolio implications as governments and central banks begin to reduce economic stimulus.

It has been thought that without growth in the money supply, economic growth would fall below what is politically and socially acceptable.

But, as Ray Dalio[1], founder of the world’s largest hedge fund (Bridgewater Associates) explains, the economy is essentially the sum of all spending, and inflation is an increase in average prices for goods, services and assets.

Credit is the most important part of the economy as one person’s spending is another person’s income, facilitating more spending.

Most sovereign nations have enormous debt, which they will need to reduce or deleverage. Confidence that countries can pay back debt is very important.

Dalio points out four methods which governments can employ to pay back debt:

- The first and most popular option, is monetisation– at its peak right now. Basically, central banks print money to buy financial assets like bonds. This lowers returns from “safe” investments and pushes investors up the risk curve, driving up asset prices, but exacerbating wealth inequality and societal tension. It is no coincidence that booms in high-growth equities, house prices and speculative assets like crypto have followed.

- The second is austerity, where people and governments cut spending to reduce credit creation and pay down debt. Spending cuts result in falling incomes, unemployment, and worsening debt burdens, which is deflationary and painful. Europe experimented with this in 2012.

- The third is mass default, when borrowers don’t repay, banks get squeezed, bank runs happen and assets are sold for fire sale prices. Financial wealth is crushed, leading to economic depression. China is attempting to manage a controlled default in its over-levered property sector right now.

- The fourth is wealth distribution or revolution, where wealth is redistributed from haves to have nots. This is often facilitated through higher taxes, which raises social and political tensions, like what we have seen in American politics.

The difficulty that central banks face is that by buying government bonds, they give governments cheaper financing to run deficits.

Policy makers have to balance scaling back money creation and spending. They need to slow inflation, but at a pace that doesn’t shrink income growth below debt growth.

Current financial market volatility is due to trying to price assets against dual risks:

- that long-term inflation will erode the purchasing power of investment returns;

- if policy makers withdraw stimulus too quickly, they remove the force that drove asset prices up in the first place.

So, how do these forces affect your portfolios?

Well, global financial markets will be more volatile in our view, with aggressive monetary tightening expected over the next few years, potentially leading to recession.

The war in Ukraine has highlighted the acute vulnerabilities that the world has to shortages in fossil fuel supply, which has direct impacts on the cost of energy and food (via fertiliser costs).

Incidentally, this has been exacerbated by underinvestment in fossil fuel supply due to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) concerns by those in a position to allocate capital. These forces will not resolve soon and will feed into higher inflation expectations and lower consumer sentiment.

Amidst this regime change to higher inflation and higher interest rates, government bonds and equities have become increasingly correlated, increasing the risk and reducing the return potential of typical investment portfolios around the world.

The prospect of the developed world’s rapidly aging population drawing down savings to fund retirement complicates the picture further. Investment strategies that can profit from volatility and stay liquid, irrespective of interest rate movements, are likely to be highly sought.

Credit markets generate higher levels of short-term cash than government bonds but could suffer if economic conditions worsen. Strategies that are flexible enough to find pockets of value in defensive sectors, and not overly exposed to lending long to generate yield, may be sensible choices.

What happens when governments reduce economic stimulus?

Removing “monetisation” support for risk assets like listed equities, private equity, real assets and crypto is likely to create a wide range of outcomes.

Many emerging markets, trading on attractive valuations with solid government finances, powerful long-term demographic trends and dynamic growth industries, have potential, in Fidante’s view.

In a general sense, active management and investing based on valuation and fair price, as opposed to potential, but unproven, future growth prospects, are more likely to be prospective in a world with less money creation.

Decarbonisation a game-changer

Finally, decarbonisation and natural resource management will be one of the biggest macro trends of our lifetimes. This will have big impacts on future inflation expectations. But the transition will not be seamless, as the gas supply tensions in Europe and oil price spikes show.

Concerns over water and food supplies in places like Asia and Africa will be acute. The Ukraine invasion has effectively removed around a quarter of the world’s traded wheat from markets that would otherwise come from the rich black soils of Ukraine and south-western Russia. The snow melts that power the great rivers and agriculture of India, Southeast Asia and China are under threat from climate change.

Trillions will be needed to upgrade energy transmission, build solar, wind, geothermal and hydropower and invest in R&D game-changers like fusion power and new battery technologies. Modern nuclear power like molten salt reactors will need to be considered, but this is a political minefield.

Competition for access to metals like nickel, cobalt and lithium as well as rare earths will be key considerations for decades to come. The effects of higher energy costs and water scarcity on agricultural production could result in more volatility in food supply and prices.

As investors, corporations and governments exercise their capital allocation preferences towards more sustainable business models, the risk of investing in stranded industries and assets rises, even if those industries are still critical.

But right now, the world has too much money. The biggest question for markets is what happens next. Investors have a key role to play in directing their money towards funding the future we want for our children.

the founder of Bridgewater Associates, who offers his perspective on how the ‘economic machine’ works in a 30-minute video at www.economicprincipals.org. It’s as good an explanation of economics 101 as I’ve ever seen.

A big thank you to Ashurst for their publication The Pulse which I have attached for your light reading.

I hope you have enjoyed this week’s read. If you would like to discuss your investment options, please feel free to give me a call

Regards,

Chris Hagan.

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

Level 1, Harbourside West, Stanley Esplanade

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814